Red Alert II: An Update on Postpartum Hemorrhage

https://gexinonline.com/archive/journal-of-comprehensive-nursing-research-and-care/JCNRC-144

2Doctoral student, Loyola University of Chicago. USA.

Recently, a model to predict excessive blood loss after delivery was developed from a retrospective cohort study of 2236 deliveries in Spain [12]. The model included maternal age, primiparity, duration of first and second stages of labor, neonatal birth weight, and antepartum hemoglobin. Such evidence-based models can assist clinicians to evaluate the impact of multiple risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage on individual patients.

The identification of maternal risk factors includes a thorough history upon admission to labor/delivery and careful review of the prenatal record. The nurse also needs to be vigilant for risk factors that emerge during the labor process. Awareness of risk factors can prevent a serious blood loss, or expedite appropriate treatment.

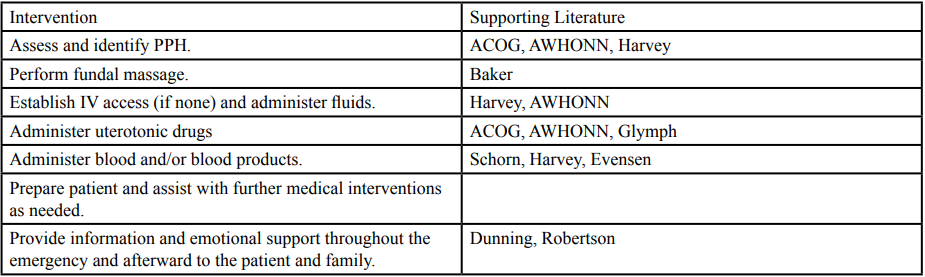

Management of postpartum hemorrhage is dependent upon the cause as previously stated: Tone, tissue, trauma and thrombin. Each causative factor has initial interventions. The initial interventions, if not successful, may be followed by accompanying therapies.

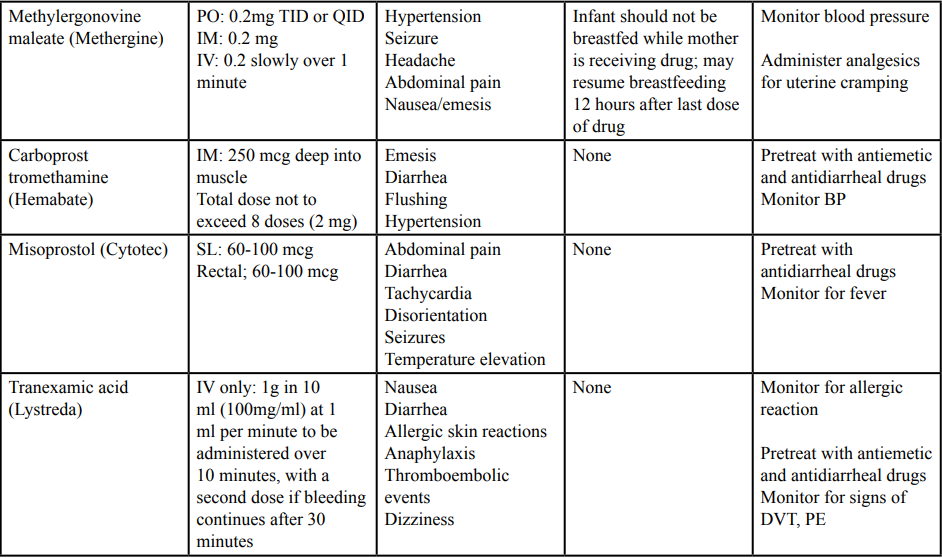

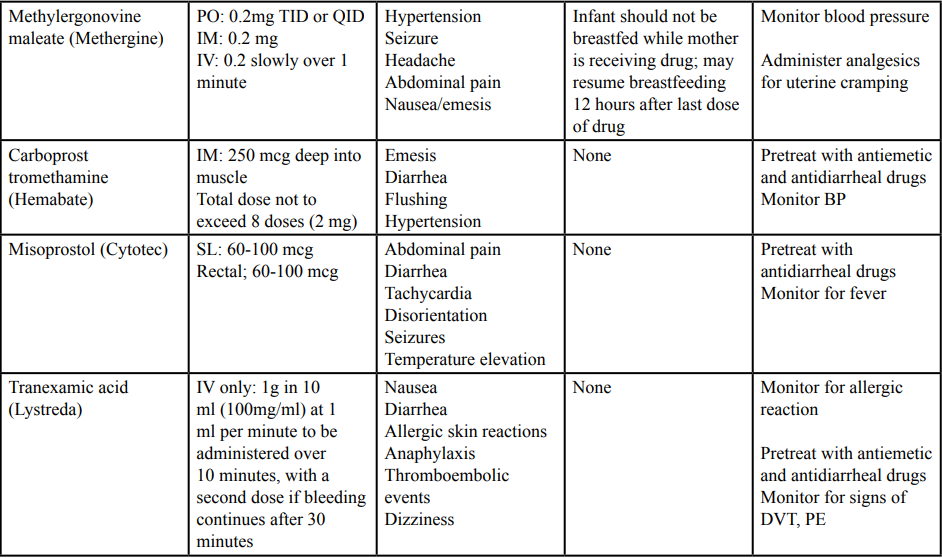

If the root cause of the hemorrhage is uterine atony (tone), the first step is to massage the uterus to expel any clots [14]. If there is no response, IV drug therapy with uterotonic agents (oxytocin, methylergonovine, 15-methyl prostaglandin) is indicated (3; Table 2). Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has updated its recommendations for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage to include the administration of tranexamic acid (an antifibinolytic) as soon as possible after the onset of bleeding and within three hours of delivery [15]. This recommendation was based upon the results of the WOMAN trial, published in 2017 [16]. If the hemorrhage is not stopped with these measures, uterine balloon tamponade, uterine compression suture or uterine artery embolization maybe utilized [3,17]. Hysterectomy is the last resort to contain postpartum hemorrhage if the variety of interventions previously discussed fail to control the bleeding [18].

Table 2: Medications Used in the Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage (Adapted from Glymph and drug rxlist).

Treatment of postpartum hemorrhage caused by problems with

tissue focus on identifying and treating adherence and invasion of

the placenta into the uterine wall: Placenta accreta, placenta increta,

and placenta percreta. Harvey [6] uses the term morbidly adherent

placenta (MAP) in describing the placental pathology of this group

of conditions. Harvey defines each placental abnormality. Placenta

accreta is the abnormal adherence of the placenta to the uterine wall

which does not detach after delivery. Placenta increta occurs when

the placental invasion extends into the uterine muscle. Placenta

percreta is the invasion of the placenta through the myometrium and

serosa and may even extend into the bladder and adjacent organs.

Table 2: Medications Used in the Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage (Adapted from Glymph and drug rxlist).

Treatment of postpartum hemorrhage caused by problems with

tissue focus on identifying and treating adherence and invasion of

the placenta into the uterine wall: Placenta accreta, placenta increta,

and placenta percreta. Harvey [6] uses the term morbidly adherent

placenta (MAP) in describing the placental pathology of this group

of conditions. Harvey defines each placental abnormality. Placenta

accreta is the abnormal adherence of the placenta to the uterine wall

which does not detach after delivery. Placenta increta occurs when

the placental invasion extends into the uterine muscle. Placenta

percreta is the invasion of the placenta through the myometrium and

serosa and may even extend into the bladder and adjacent organs.

Medical management consists of identifying factors in the patient’s history which may indicate placental abnormalities, if not discovered before delivery through ultrasound testing. Depending upon the severity and persistence of the adherent or invasive placenta, the patient is moved into the operating room for procedures such as curettage, wedge resection, or hysterectomy [3].

Postpartum hemorrhage caused by tissue trauma can range from simple genital tract lacerations to uterine inversion [8]. Treatment of lacerations involves suturing; more extensive trauma requires surgical intervention. Again, identifying risk factors such as precipitous delivery and macrosomia can alert the medical team that intervention may be necessary.

Recognition of preexisting bleeding disorders (thrombin) and complications that can arise from massive transfusion is an important aspect of medical management [6]. Treatment of the underlying cause of postpartum hemorrhage is critical in order to achieve the goal of minimizing blood loss [9,10]. Treatment for this cause of postpartum hemorrhage may often occur in an intensive care setting.

Physical assessment of the postpartum patient includes breast assessment, (a good time to teach breast self-examination techniques) to determine readiness for breast feeding. Assessment also includes the very important evaluation of fundal height for firmness, identification of any lacerations, bladder distention and continuous analysis of blood loss. Vital signs (temperature, respirations, pulse are monitored for any signs of hemodynamic instability [17].

Should the uterine tone remain boggy, uterotonic drugs are administered. These drugs include oxytocin (Pitocin), prosta-glandin E1 (Misoprostol), methylergonovine (Methergine), 15- Methylprostaglanding (Hemabate) [21]. The World Health Organization has recently updated it recommendations for uterotonic medications to include Transexamic Acid to be used in the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage [22]. (See table 3).

Although treatment of postpartum hemorrhage with blood transfusions is actually dependent upon the assessment and judgment of clinicians at the bedside, transfusion protocols are important [6,24]. ACOG [3] guidelines recommend transfusion for blood loss greater than 1500 cc, or the development of maternal tachycardia or hypotension. Platelets and coagulation factors must also be administered. ACOG [3] defines massive transfusion as greater than 10 units of packed red blood cells with 24 hours, or 4 units within an hour.

Being prepared for transfusion is crucial. Butwick [27] recommends blood typing for low risk patients, type and screening for patients at moderate risk, and type and crossmatch for patients at high risk for postpartum hemorrhage. Multiple authorities advocate the use of transfusion protocols that can be rapidly implemented [3,6,24,26]. However, this life-saving therapy is not without risk. Transfusion has been found to correlate with maternal morbidity and hysterectomy [28]. Potential complications include hypothermia, metabolic acidosis, and coagulopathy [6]. The nurse must be aware of any developing complication when transfusing the postpartum patient and take appropriate measures to mitigate these potentially deadly situations.

Programs that include multiple modes of education such as didactic, skills, stations and simulation have been shown to improve the quality of care delivered to patients experiencing postpartum hemorrhage [38-41]. Mansfield [42] found that auditing the process of responding to postpartum hemorrhage increased the speed and quality of teamwork. The lean process has been applied to postpartum hemorrhage [43]. The lean process (management strategies used in Japanese manufacturing applied to health care) involves analyzing the steps of the response to postpartum hemorrhage and eliminating those steps that do not add value or meet the patient’s needs. This analysis helps streamline nursing care and increase its efficiency.

The importance of care bundles has been mentioned by many authors [2,3,6,43] When evidence based care bundles are implemented promptly, they increase the probability of reaching the goals of treatment [40]. This applies to all interventions implemented for postpartum hemorrhage, particularly for transfusion, as discussed earlier.

Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 3 (2018), Article ID: JCNRC-144

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100144Review Article

Red Alert II: An Update on Postpartum Hemorrhage

Nancy J. MacMullen1, Laura A. Dulski2, Linda F. Samson1*

1Department of Nursing, Governors State University, 1 University Parkway, University Park, IL 60484, USA.

2Doctoral student, Loyola University of Chicago. USA.

Corresponding Author Details:

Linda F. Samson, Department of Nursing, Governors State University, 1 University Parkway,

University Park, IL 60484, USA.

E-mail: lsamson@govst.edu

Received date: 17th January, 2019

Accepted date: 13th July, 2019

Published date: 15th July, 2019

Accepted date: 13th July, 2019

Published date: 15th July, 2019

Citation: Macmullen NJ, Dulski LA, Samson LF (2019) Red Alert II: An Update on Postpartum Hemorrhage. J Comp Nurs

Res Care 4: 144.

Copyright: ©2019, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author

and source are credited

Abstract

Obstetric hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal mortality, with most occurring in the postpartum period. Postpartum hemorrhage during the first 24 hours after delivery is defined as primary postpartum hemorrhage and is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide including the United States. Estimates of mortality vary and are difficult to compare because of the manner of presentation. A research study from Pakistan reported almost 25 percent of maternal deaths in a single hospital sample set were related to postpartum hemorrhage while data from South Africa reported obstetric hemorrhage during the period 2008-2010 was 24.9 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. This is an increase from the previous triennium when the total maternal deaths due to obstetric hemorrhage was 18.8 per 100,000 live births. In the only U.S. mortality and morbidity data for a comparable period, California reported that morbidity appeared to be linked to the type of hospital where care was delivered, however the study used secondary data sources. This article reviews causative risk factors and examines the latest evidence based care options. The article also explores associated risk factors, assessment and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, with an emphasis on providing evidence-based nursing care to the patient experiencing a primary postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery.Nursing Implications for Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage impacts maternal morbidity and mortality globally, including the United States [1]. This is particularly true in rural areas or less developed countries where there is a lack of medical and nursing professionals who are prepared to deliver the appropriate care. Since nurses are often the first persons to respond to a patient experiencing a postpartum hemorrhage, it is extremely important for them to act quickly and efficiently to minimize maternal blood loss. Postpartum hemorrhage is an emergency requiring the rapid choice of the most appropriate nursing interventions in an urgent situation. It is the purpose of this paper to examine the evidence contained in the health care literature to determine the most effective nursing interventions for primary postpartum hemorrhage occurring in the patient who has experienced a vaginal delivery and to present a case study for nursing care consideration.Definition of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Several authorities provide similar definitions of postpartum hemorrhage. The World Health Organization defines postpartum hemorrhage as “blood loss greater than or equal to 500 ml. within 24 hours after birth, while severe postpartum hemorrhage is blood loss greater than or equal to 1000 ml within the same time frame” [1]. The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) describes postpartum hemorrhage as “500 ml. within 24 hours after birth” [2]. However, they do not define severe postpartum hemorrhage. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) [3] discusses severe postpartum hemorrhage in a slightly different manner. The organization categorizes a severe postpartum hemorrhage as” a cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1000mL or blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after the birth process (includes intrapartum loss), regardless of route of delivery" [3]. Primary postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) occurs within the first twenty- four hours of birth; secondary postpartum hemorrhage occurs more than twenty-four hours after delivery and up to twelve weeks after delivery [4]. Regardless of the definition, the nurse must recognize and intervene for women who are experiencing postpartum hemorrhage. In addition to definitions found in the United States literature, there are several definitions found in the in the international literature that use the World Health Organization (WHO) as the defining organization. Like AWHONN and ACOG the volume of blood loss in the first 24 hours after delivery is the same 500 ml, however authors cite difficulty in quantifying the exact amount of blood loss and indicate that it is frequently underestimated [4]. There is also acknowledgement that the definition of severe postpartum hemorrhage is variable across credible sources although 1000 ml in 24 hours post- delivery appears to be the most commonly accepted threshold. Hemodynamic instability is an important part of diagnosis and a smaller blood loss may be significant in a severely compromised woman [5].Epidemiology of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Trends indicate that the number of pregnancy-related deaths in the United State have consistently increased from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 18.0 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2014 [6]. Of these deaths, the CDC [7] data shows that the maternal mortality from all types of pregnancy/post pregnancy related hemorrhage is 11.5 %. Data published by AHRQ presents the rate of maternal deaths from postpartum hemorrhage globally as 6 to 11 percent of births; in the United States it is 2.9 percent [8]. Unfortunately, postpartum hemorrhage accounts for nearlyone quarter of all maternal deaths globally andis the leading cause of maternal mortality indeveloping countries, with rates as high as sixty percent in some countries [1].Etiology

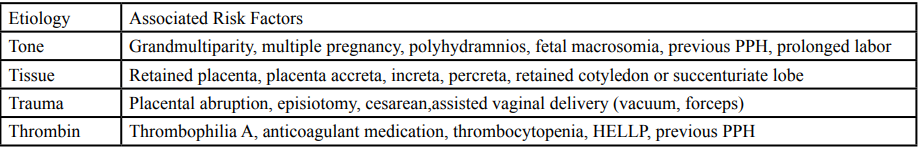

The causes of PPH have been categorized into the “4Ts’: tone, tissue, trauma and thrombin [9,10]. A majority of postpartum hemorrhage occurs secondary to uterine atony, which is impaired contractility of the uterus after delivery, resulting in a large blood loss. Estimates of the percent of PPH caused by uterine at any range from 75- 90 percent of all cases [11]. Retained placental tissue prevents the uterus from contracting post-delivery. Abnormal adherence of the placenta (acreta, percreta, increta) also affects uterine contractility [3] Cervical, vaginal, or perineal lacerations can cause large amounts of blood loss, particularly if undetected. Maternal coagulation disorders, either congenital, iatrogenic, or developing from events such as placental abruption, amniotic fluid embolism, and severe preeclampsia, prevent the normal hemostasis that occurs once the third stage of labor is complete. Secondary postpartum hemorrhage can occur with subinvolution of the placental site; retained products of conception, and infection [3,6]. Each of the “4 Ts” has associated risk factors that need to be identified and monitored during the birth process.Risk Factors

Risk factors associated with tone include conditions that impair uterine contractility such as grandmultiparity, overdistension of the uterus, and previous postpartum hemorrhage [9] (see table 1. Risk factors associated with tissue have to do with either incomplete separation of the placenta during the third stage of labor, or abnormal placental implantation [9] (see table 1. Lacerations of the genital tract during delivery, operative vaginal delivery, and cesarean section are all risk factors associated with trauma [9] (see table1). Finally, risk factors associated with thrombin include thrombocytopenia, thrombophilia A, the use of anticoagulant medication, and HELLP syndrome [9] (see table 1).Recently, a model to predict excessive blood loss after delivery was developed from a retrospective cohort study of 2236 deliveries in Spain [12]. The model included maternal age, primiparity, duration of first and second stages of labor, neonatal birth weight, and antepartum hemoglobin. Such evidence-based models can assist clinicians to evaluate the impact of multiple risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage on individual patients.

The identification of maternal risk factors includes a thorough history upon admission to labor/delivery and careful review of the prenatal record. The nurse also needs to be vigilant for risk factors that emerge during the labor process. Awareness of risk factors can prevent a serious blood loss, or expedite appropriate treatment.

Medical Management

Prevention is the first step in medical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Aside from the identification of maternal risk factors, there are several interventions that can help prevent excessive bleeding after delivery. These interventions include the administration of oxytocin, delayed cord clamping, draining the placenta of blood, controlled cord traction, and uterine massage [13]. ACOG also recommends active management of the third stage of labor to reduce the probability of postpartum hemorrhage [3]. There are three components of active management:(1) oxytocin; (2) uterine massage; and (3) umbilical cord traction [3].Management of postpartum hemorrhage is dependent upon the cause as previously stated: Tone, tissue, trauma and thrombin. Each causative factor has initial interventions. The initial interventions, if not successful, may be followed by accompanying therapies.

If the root cause of the hemorrhage is uterine atony (tone), the first step is to massage the uterus to expel any clots [14]. If there is no response, IV drug therapy with uterotonic agents (oxytocin, methylergonovine, 15-methyl prostaglandin) is indicated (3; Table 2). Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has updated its recommendations for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage to include the administration of tranexamic acid (an antifibinolytic) as soon as possible after the onset of bleeding and within three hours of delivery [15]. This recommendation was based upon the results of the WOMAN trial, published in 2017 [16]. If the hemorrhage is not stopped with these measures, uterine balloon tamponade, uterine compression suture or uterine artery embolization maybe utilized [3,17]. Hysterectomy is the last resort to contain postpartum hemorrhage if the variety of interventions previously discussed fail to control the bleeding [18].

Table 2: Medications Used in the Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage (Adapted from Glymph and drug rxlist).

Table 2: Medications Used in the Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage (Adapted from Glymph and drug rxlist).Medical management consists of identifying factors in the patient’s history which may indicate placental abnormalities, if not discovered before delivery through ultrasound testing. Depending upon the severity and persistence of the adherent or invasive placenta, the patient is moved into the operating room for procedures such as curettage, wedge resection, or hysterectomy [3].

Postpartum hemorrhage caused by tissue trauma can range from simple genital tract lacerations to uterine inversion [8]. Treatment of lacerations involves suturing; more extensive trauma requires surgical intervention. Again, identifying risk factors such as precipitous delivery and macrosomia can alert the medical team that intervention may be necessary.

Recognition of preexisting bleeding disorders (thrombin) and complications that can arise from massive transfusion is an important aspect of medical management [6]. Treatment of the underlying cause of postpartum hemorrhage is critical in order to achieve the goal of minimizing blood loss [9,10]. Treatment for this cause of postpartum hemorrhage may often occur in an intensive care setting.

Methods

This integrative review of the literature was conducted using the databases of EBSCO and CINAHL, as well as the Joanna Briggs Institute database. All pertinent literature from 2013 to 2018 was examined using the search words “postpartum hemorrhage“ primary postpartum hemorrhage, “nursing care of postpartum hemorrhage”, “medical management of postpartum hemorrhage”, “WHO”; “CDC”. ” ACOG”, and “AWHONN”. The authors then synthesized the information in these articles for this publication.Literature Review

The literature review focused on evidence supporting nursing interventions for patients experiencing primary postpartum hemorrhage. Secondary postpartum hemorrhage, hemorrhage related to cesarean section, and complications of postpartum hemorrhage were not addressed due to the authors’ desire to limit the scope of the paper.Nursing Assessment

A thorough nursing assessment of the patient’s prenatal and delivery history is crucial as the first step in identifying the potential for postpartum hemorrhage. Risk factors for hemorrhage may be identified, one of which is previous postpartum hemorrhage [11]. Review of the history may also reveal any underlying medical condition which may impact maternal hemodynamic stability. Previous delivery complications such as a prolonged third stage are associated with postpartum hemorrhage and alert the nurse to potential for hemorrhage in the current situation, if noted in the patient’s history [19,20].Physical assessment of the postpartum patient includes breast assessment, (a good time to teach breast self-examination techniques) to determine readiness for breast feeding. Assessment also includes the very important evaluation of fundal height for firmness, identification of any lacerations, bladder distention and continuous analysis of blood loss. Vital signs (temperature, respirations, pulse are monitored for any signs of hemodynamic instability [17].

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions are dependent upon the etiology of the primary postpartum hemorrhage: Tone, tissue trauma and thrombin discussed earlier. Interventions proceed from least invasive to most inva-sive [6]. Since uterine atony is the cause of a majority of postpartum hemorrhage, interventions are first directed at addressing the causes of loss of tone [6].Tone

If the fundus is not firm (boggy), fundal massage is indicated [17]. The cause may be related to postpartum pathology or to a full bladder, which inhibits fundal involution. Therefore, the nurse has the patient empty her bladder [3]. If the patient is unable to empty her bladder, an order for urinary catheterization is obtained and catheterization is employed.Should the uterine tone remain boggy, uterotonic drugs are administered. These drugs include oxytocin (Pitocin), prosta-glandin E1 (Misoprostol), methylergonovine (Methergine), 15- Methylprostaglanding (Hemabate) [21]. The World Health Organization has recently updated it recommendations for uterotonic medications to include Transexamic Acid to be used in the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage [22]. (See table 3).

Tissue

The nurse prepares the patient and assists with any necessary medical interventions related to the abnormal implantation of the placenta. As recommended by AWHONN [2], blood loss is closely monitored and the patient is assessed for signs of hypovolemic shock.Trauma

If the patient continues to bleed, and the uterus is firm, tissue trauma is suspected (14) Baker [14], states that the perineal area should be assessed to determine if there is any tissue disruption, such as lacerations or hematoma The physician or advanced practice nurseis then called to evaluate further. The nurse should prepare the patient for surgery to repair the laceration or evacuate the hematoma if indicated.Thrombin

Assessment of the patient’s history for bleeding disorders is essential for patient safety during and after delivery. The nurse needs to assure that a transfusion protocol can be rapidly implemented [6]. Coagulopathies such as disseminated intravascular coagulation are avoided by the judicious use of blood products [6].Fluids/transfusion

If postpartum bleeding is not stopped promptly, it can lead to hypovolemic shock [4]. The goal of maternal stabilization is to stop the blood loss before it leads to severe morbidity and mortality (Harvey). Crystalloid fluids should be given for fluid replacement until the blood loss becomes severe, then transfusion should be rapidly initiated [6,23,24] Large volumes of crystalloid fluids can cause dilutional disseminated intravascular coagulation [6] AWHONN [2] recommends that maternal blood loss be quantified as closely as possible. When weighing saturated articles, 1 gram is equivalent to 1 milliliter of blood loss [2]. Hemodynamic resuscitation includes restoration of circulating volume and blood component therapy [25,26]. A rapid response should be initiated if maternal heart rate is at or above 110 beats/minute, blood pressure less than or equal to 85/45, or a 15 % or greater change from the baseline, or oxygen saturation less than 95% [6].Although treatment of postpartum hemorrhage with blood transfusions is actually dependent upon the assessment and judgment of clinicians at the bedside, transfusion protocols are important [6,24]. ACOG [3] guidelines recommend transfusion for blood loss greater than 1500 cc, or the development of maternal tachycardia or hypotension. Platelets and coagulation factors must also be administered. ACOG [3] defines massive transfusion as greater than 10 units of packed red blood cells with 24 hours, or 4 units within an hour.

Being prepared for transfusion is crucial. Butwick [27] recommends blood typing for low risk patients, type and screening for patients at moderate risk, and type and crossmatch for patients at high risk for postpartum hemorrhage. Multiple authorities advocate the use of transfusion protocols that can be rapidly implemented [3,6,24,26]. However, this life-saving therapy is not without risk. Transfusion has been found to correlate with maternal morbidity and hysterectomy [28]. Potential complications include hypothermia, metabolic acidosis, and coagulopathy [6]. The nurse must be aware of any developing complication when transfusing the postpartum patient and take appropriate measures to mitigate these potentially deadly situations.

Pharmacological management

The medications utilized to treat postpartum hemorrhage are called uterotonic drugs. They cause uterine contraction, and therefore stop the bleeding. Obstetric nurses often become complacent administering these medications because they are so frequently given. Oxytocin, the most common medication, can cause serious complications such as cardiac arrhythmias, uterine rupture, and water intoxication if not closely monitored [21,29]. Methergine is contraindicated in women with hypertension, and the mother should not breastfeed while receiving the drug, and 12 hours after discontinuation [21,30]. The nurse should promote comfort for the patient by offering analgesics for the accompanying uterine cramping. When giving Hemabate or Cytotec, the nurse should be aware that these medications cause gastrointestinal distress and be ready to treat with antiemetics and or/antidiarrheal drugs [21,31,32]. Lystreda, a new medication being used to treat postpartum hemorrhage, has an anitfibrinogenolytic effect [33]. Patients should be closely monitored for signs of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, two complications that the woman is already prone to develop due to the normal hypercoaguability of postpartum.Emotional support

With the many technical interventions dominating the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, the emotional support of the patient can be neglected. Dunning, Harris and Sandall [34] found that women who had experienced postpartum hemorrhage would like more information given to them. Keeping patients informed during a crisis is important. Ekerdal et. al [35] found no association between postpartum hemorrhage and postpartum depression, but did find that women discharged with anemia were more prone to depression. Nurses who discharge these women should give them anticipatory guidance and resources. Postpartum hemorrhage can lead to psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder [36]. The mental health of the woman who has experienced postpartum hemorrhage cannot be ignored.Case Study

Mrs. M. was a 39 year old Gravida 7 Para 5 Spontaneous Abortion 1 when she presented to the local hospital in active labor. She has a history of rapid deliveries and had a postpartum hemorrhage with her last pregnancy. On admission you find her vital signs to include BP 118/68, Temperature 36.8 C, Pulse is 88. FHT’s 144. On palpation you assess that the fetus appears to be large for her estimated 38 weeks gestational age but she does not report any concerns about blood glucose or BP during her pregnancy. On initial vaginal exam the cervix is 6cm, 80% effaced and the head is at -1station. Mrs. M. does not plan to have anything but local anesthetic if needed at the time of delivery for an episiotomy although she did not have one with her last two pregnancies. She did have a 3rd degree laceration with her last delivery due to an uncontrolled delivery. Her PPH was the result of uterine atony but required several interventions to reverse. As you plan for the imminent delivery of Mrs. M and her infant what things from this article do you need to consider as: 1) risk factors for this delivery, 2) assessments that should be made during and immediately following Mrs. M’s delivery, and 3) the types of immediate interventions you should be prepared for clinically and to support Mrs. M and her family after the delivery?Evaluation of Interventions

Even though evidence-based interventions for postpartum hemorrhage may be implemented, they do not always achieve the desired outcome of stopping the bleeding before adverse outcomes occur. Interventions must be evaluated and continuously improved. AWHONN conducted a quality improvement project aimed at increasing the quantification of blood loss, risk assessment, and the use of debriefing [37]. Improvement occurred in all of these areas following an educational program, but the processes were found to not be fully implemented.Programs that include multiple modes of education such as didactic, skills, stations and simulation have been shown to improve the quality of care delivered to patients experiencing postpartum hemorrhage [38-41]. Mansfield [42] found that auditing the process of responding to postpartum hemorrhage increased the speed and quality of teamwork. The lean process has been applied to postpartum hemorrhage [43]. The lean process (management strategies used in Japanese manufacturing applied to health care) involves analyzing the steps of the response to postpartum hemorrhage and eliminating those steps that do not add value or meet the patient’s needs. This analysis helps streamline nursing care and increase its efficiency.

The importance of care bundles has been mentioned by many authors [2,3,6,43] When evidence based care bundles are implemented promptly, they increase the probability of reaching the goals of treatment [40]. This applies to all interventions implemented for postpartum hemorrhage, particularly for transfusion, as discussed earlier.

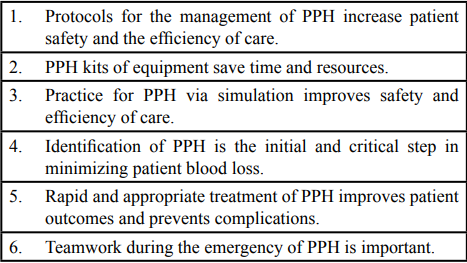

Conclusions

The literature regarding postpartum hemorrhage is clear on several issues. Identifying and treating postpartum hemorrhage early decreases maternal blood loss [3]. Protocols for the management of postpartum hemorrhage should be in place and rapidly implemented [2,3,6]. Commonly used medications and equipment need to be assembled in easily accessed kits. Processes of care delivery require continuous evaluation to ensure quality and evidence-based nursing care [43]. Team education, particularly simulation, can improve team confidence and performance during postpartum hemorrhage [38-41]. Bringing these conclusions from the literature to the bedside can help improve the outcomes of nursing care for women experiencing postpartum hemorrhage.Conflict of Interest

Authors report there is no conflict of interest of any kind and attests to the originality of this work.References

- World Health Organization (2012) WHO recommendations for

the prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage.

View

- Harvey CJ, Dildy GA (2012) obstetric hemorrhage Association

of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses.

-

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

(2017) ACOG Practice Bulletin #183, October e 168 130 4:

e168-e186.View

- Knight M, Callaghan W, Berg C, Alexander S, Bouvier-Colle M

et al. (2009). Trends in postpartum hemorrhages in high resource

countries; a reviewand recommendations from the international

postpartum hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC Pregnancy

and Childbirth 9 [55].View

- Sultana M, Irum N, Karamat H (2018) Primary postpartum

hemorrhage causativefactors, treatment outcome and its

consequences. Professional Med J 25: 966-970.View

- Harvey CJ (2018) Evidence-based strategies for maternal

stabilization and rescue in obstetric hemorrhage AACN Adv

Critical Care 29: 284-294.View

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Pregnancy mortality

surveillance system Causes of pregnancy related deaths in the

United States 2011-2014.View

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective

healthcare program management of postpartum hemorrhage:

Current state of the evidence clinical summary July 12,2016.

- Weeks A (2014) The prevention and treatment of postpartum

hemorrhage: What we know, and where do we go for next? Brit

J Obstet Gynecol 122: 202-210.View

- Sebghati M, Chandraharan E (2017) An update on the risk

factors for management ofobstetric hemorrhage Women’s

Health 13: 34-40.View

- Lalonde AB, Davis BA, Acosta A, Hershderfer K (2006

Postpartum Haemorrhage Today: Living in theShadow of the

Taj Mahal. In: B-Lynch C, KeithIG, Lalonde AB, Karoshi M

[eds]. Textbook of Postpartum Haemorrhage. Dumfriesshire,

UK. SapiensPublishing 2-9.

- Rubio-Alvaez A, Molina-Alarcon M, Arias-Arias A, HernandezMartinez A (2018) Development and validation of a predictive

model for excessive postpartum blood loss: A retrospective

cohort study Int J Nurs Studies 79: 114-121.View

- de Castro-Perreira, MVB, Ferriera Gomez N (2013) Preventing

postpartum hemorrhage: active management of the third stage

of labor J Clini Nurs 22: 3372-3387. View

- Baker K (2014) How to manage primary postpartum hemorrhage

Midwives 4: 34-35. View

- World Health organization (2017) Updated WHO

recommendation on tranexamic acid in the treatment of

postpartum haemorrhage Geneva, Switzerland; 2017 License:

CCBY-NC-SA3.0 IGO.WHO/RHR/17.21. View

- Woman’s Health Trial Collaborators (2017) Effect of early

tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy,

and other morbidities in women with post-partum hemorrhage

(WOMAN): An interventional, randomised, double blind,

placebp-controlled trial The Lancet 389: 2105-2116.View

- Dildy GA (2018) How to prepare for postpartum hemorrhage

Contemporary OBGYNE.NET , 22-31 Acccessed December 6,

2018 .View

- Abdul-Kadir et.al. (2014) Evaluation and management of

postpartum hemorrhage: consensus from an international expert

panel Transfusion practice Transfusion 4: 1756-1758.

View

- Frolova A, Stout MJ, Tuul MG, Lopez JD, Macones GA

et al. (2016) Duration of the thirid stage of labor and risk of

postpartum hemorrhage Obste gynecol 127: 5.

- Rabie NZ, Ounpraseuth S, Hughes D, Lang P, Weigel M et al.

(2018) Association of the length of the third stage of labor ad

blood loss following vaginal delivery Southern Med J 111: 3.

View

- Glymph DG, Tuborg TD, Vedenikina M (2016) Use of

tranexamic acid in preventing postpartum hemorrhage AANA

J 84: 427-438.

View

- World Health Organization (2017) Updated WHO

recommendation on tranexamic acid for the treatment of

postpartum hemorrhage 1-4.

View

- Schorn MN, Phillips JC (2014) Volume replacement following

sever postpartum hemorrhage J Midwifery Women’s Health 59:

336-343.

View

- Evensen, A, Andersen JM, Fontaine P (2017) Postpartum

hemorrhage prevention and treatment American Family

Physician 95: 442-451.

View

- Ruth D, Kennedy BB (2011) Acute volume resuscitation

following obstetric hemorrhage. J Perinatal Neonatal Nurs 25:

253-260.

View

- Pacheco LD, Saade CR, Constantine MM, Clark SL Hankins

GDV (2016) An update on the use of massive transfusion

protocols in obstetrics Am J Obste Gynecol 340-344.

- Butwick AJ, Goodnough LT (2015) Transfusion and coagulation

management in major obstetric hemorrhage Anesthesiology 28:

3.

View

- Green L, Knight M, Seeney Fm, Hopkinson C, Collins PW

(2015) The epidemiology and outcomes of women with

postpartum hemorrhage requiring massive transfusion with

eight or more units of red cells: A national cross-sectional study

Brit J Obste Gynecol 2164-2170.

View

- Pitocin

- Methergine.

- Hemabate.

- Cytotec.

- Lystreda.

- Dunnung T, Harris Jm, Sandal J (2016) Women and their

birth partners’ experiences following a primary postpartum

hemorrhage: A qualitative study BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

16: 80.

View

- Ekerdal P, Kollia N, Lofbled J, Hellgren C, Karlson L et al.

(2016) Delineating the association between heavy postpartum

haemorrhage and postpartum depression PloS ONE 11.

View

- Robertson J, Kehler S, Meuser A, MacDonald T, Gilbert J (2017)

After the unexpected: Ontario midwifery clients’ experiences of

postpartum hemorrhage Can J Midwifery Res Pract 16: 10-19.

- Bingham D, Scheich B, bateman BT (2018) structure, process

and outcome data of AWHONN’s Postpartum Hemorrhage

Quality Improvement Project, J Obste Gynecol Neonatal Nurs

47: 707-718.

View

- Bittle M, O’Rourke K, Srinivas SK (2018) Interdisciplanary

skills review program to improve team responses during

postpartum hemorrhage, J Obste Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 47:

254-263.

View

- Chagolla B, Bingham D, Wilson B, Scheich B (2018)

Perceptions of safety improvement among clinicians before

and after participating in a multistate postpartum hemorrhage

project, J Obste Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 47: 698-706.

View

- Egenberg S, Oian P, Eggeba TM, Grujic Arsenovic M, Bru LE

et al. (2016) Changes in self-efficacy, collective efficacy and

patient outcome following interprofessional simulation training

on postpartum haemorrhage, J Clini Nurs 26: 3174-3187.

View

- Letchwoth PM, Duffy Sp, Phillips D (2017) Improving nontechnical skills (teamwork) in post-partum haemorrhage: A

group randomised trial, Europ J Obste Gynecol Reprod Bology

217: 154-160.

View

- Mansfield J (2018) Improving practice and reducing significant

postpartum haemorrhage through audit, Brit J Midwifery 26:

35-43.

View

- Faulkner B (2013) Applying lean management principles to the creation of a postpartum hemorrhage care bundle Nursing for Women’s Health 17: 402-411. View

- Red Alert II: An Update on Postpartum Hemorrhage ,

- An Update on Postpartum Hemorrhage ,

- An Update on Postpartum Hemorrhage Red Alert II ,

- Red Alert Update on Postpartum Hemorrhage ,

Comments

Post a Comment