Problems with Home Care of Low-birth-weight Infants: “Use of Little Baby Handbook” to Support Low-birth-weight Infants and Families (Mothers)

https://gexinonline.com/archive/journal-of-comprehensive-nursing-research-and-care/JCNRC-135

Keywords: low-birth-weight infant, mother, Maternal and Child Health Handbook

The mothers cannot easily go out because of rearing their infants. They do not have many opportunities to receive peer support and facilities providing respite care are lacking. Although infants require services from many facilities, such as rehabilitation, multidisciplinary cooperation is undeveloped because of undeveloped communitybased integrated care systems and lack of home-visit nursing services for home care infants.

To cope with this situation, ‘Maternal and Child Health Handbook for low-birth-weight infants and their families (mothers)’ was prepared by mothers of low-birth-weight infants and utilized as rearing support for them. In this report, problems with home care of low-birth-weight infants in Japan and ‘Maternal and Child Health Handbook for low-birth-weight infants and their families (mothers)’ are introduced and the benefit of the handbook is discussed.

However, not all life-saved infants achieve sequela-free survival and many infants require continuation of medical care [4]. Insufficiency of beds in NICU due to an increase in infants hospitalized in NICU for a prolonged period caused not only difficult acceptance of neonates but also social problems, such as rejection of admission of the mothers [5]. To cope with these problems, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare specified the proper number of beds in NICU to 25-30 per 10,000 births in the Guidelines for the Establishment of Perinatal Care Systems in 2010, and promotes preparation of NICU and environments facilitating rehabilitation and medical care of home care infants according to the actual regional situations [6].

According to the nationwide estimate in 2012, about 150 infants were discharged with ventilator attachment in the year and this number is about 5 times of that (33.6) in 2004 [7]. Of ventilatorattached infants discharged within one year after admission to NICU, 46% were discharged to home, 33% and 19% transferred to internal and external pediatric wards, respectively, and 67% of them finally transferred to home care.

The growth values are low in many very low-birth-weight infants even when compared with those at the corrected age. The growth catch-up rate (increase exceeding -2SD or 2.3 percentile of infantile physical growth value) of low-birth-weight infants decreases with shortening of the period of gestation [8]. The height and body weight of infants with a birth weight lower than 750 g cannot catch up at 3 years old [9,10]. The chronological age at which they exceed the 10th percentile of the infantile physical growth value is 5 years old for the body weight and 4 and 5 years old for the height in boys and girls, respectively.

In a longitudinal survey of long-term outcomes of very low-birthweight infants (below 1,000 g), the frequency of cerebral palsy at 6 years old was 17.3% in children born in 2000 [11], whereas it was 15.5% in a survey of 6-year-old children in 1995 [12], showing a slight increase in children with cerebral palsy. The frequency of intellectual developmental disorder (70 < Intelligence Quotient)at 6 years old was 26.6% and that including the boundary zone (70 < Intelligence Quotient < 85)was 42.6%. Children with intellectual developmental disorder including the boundary zone significantly increased at 6 years old compared with that (33.2%) at 3 years old. Development of very low-birth-weight infants with no neurological disorder is still lower than the average of healthy children. For example, on an analytical infantile development test using Enjoji’s development scale, the development of low-birth-weight infants from 1 to 2 years old was below the average of healthy infants. Language understanding of low-birth-weight infants catches up with development of the corresponding age at 3 years old, but speech is still below average at 3 years old [13].

The outcome of low-birth-weight infants includes problems with severe motor and intellectual disabilities. Severe physical disability and severe intellectual disability overlap in this condition [14]. This term is used for child welfare-based administrative measures and defined as a condition with ADL up to sitting and IQ below 35 in the judgment criteria employing Oshima’s classification [15]. Infants constantly requiring medical management have rapidly increased with rapid progress in perinatal and infant medical care in Japan, although they do not meet the definition of severe motor and intellectual disabilities. Severe motor and intellectual disabilities and the necessity of constant medical care are combined in these infants and they are defined as ‘children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities, medical care dependent group (SMID-MCDG)’. Using the score of SMID-MCDG (respirator management: 10, IVH: 10, nasopharyngeal airway: 5) established by Suzuki et al. [16], infants scored 25 or higher are judged as ‘SMID-MCDG’ and those scored 10 or higher are judged as ‘sub-SMID-MCDG’ [17].

The onset time of medical care-dependent severe motor and intellectual disabilities is in the neonatal period in 67%. According to the 2007 complete enumeration inventory surveyof SMID-MCDG (nationwide 8 prefectures), 444 were SMID-MCDG and 649 were semi-SMID-MCD [18]. Medical care performed at home in 747 SMID-MCDG/semi-SMID-MCDG is as follows: tube feeding in 702 (94%), postural change in 486 (65%), tracheotomy in 354 (47%), ventilator in 171 (23%), frequent suctioning in 194 (26%), and oxygen administration in 216 (29%).

In a survey performed by Sugimoto et al. in 2007, 70% of SMID-MCDG received home care, and home-visiting nursing care station and home help service were used by 18 and 12%, respectively. Regional welfare service was not frequently used and the family mostly carries out care. The mothers mainly perform home care of SMID-MCDG, bearing a large burden. Especially, they have insomnia and chronic fatigue immediately after initiation of home care life [24] because they cannot judge the child’s symptoms and perform home care while being afraid of life crisis [25]. Moreover, the mothers require a lot of time and effort for various applications necessary for home care of infants: Applications for public expense for medical care, physically disabled persons’ certificate, and Special Child Rearing Allowance, investigation of and application for medical devices and welfare equipment for home care, and application for home modification.

The needs for rehabilitation and respite care are high in children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities and those requiring and medical care. However, utilizable social resources are lacking and social support does not catch up with the needs. In 2013, the Advisory Council on Social Security Medical Care Committee [26] proposed construction of medical care and welfare service systems necessary for home care of infants who required long-term medical treatment in NICU [27]. In 2015, the Act for Comprehensive Welfare for Persons with Disabilities proposed detailed measures for the diverse needs of children with disabilities. In 2016, the Act for Comprehensive Welfare for Persons with Disabilities and Child Welfare Act clearly stipulated children with medical care as ‘children with disabilities requiring long-term medical care’, and set the obligation of local governments to make efforts to prepare a system for liaison and coordination with institutions providing support of related fields, such as health and medical care and welfare, for these children to smoothly receive necessary support, in consideration of burdens on their families [28]. However, unlike long-term care insurance and community-based integrated care systems for adults, no common framework connecting medical care and welfare is available for pediatric home care. Accordingly, multidisciplinary cooperation is lacking and the mothers have to inevitably function as a key person to connect many facilities.

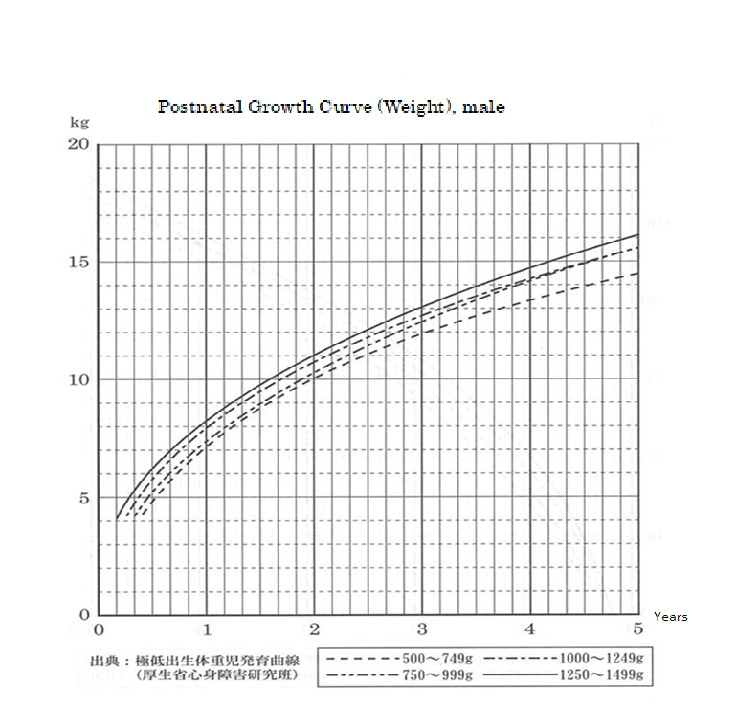

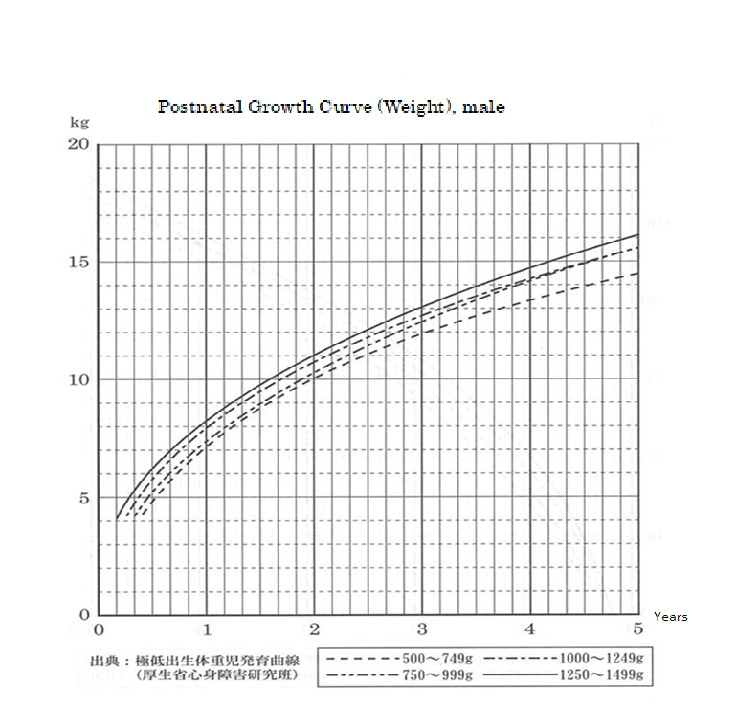

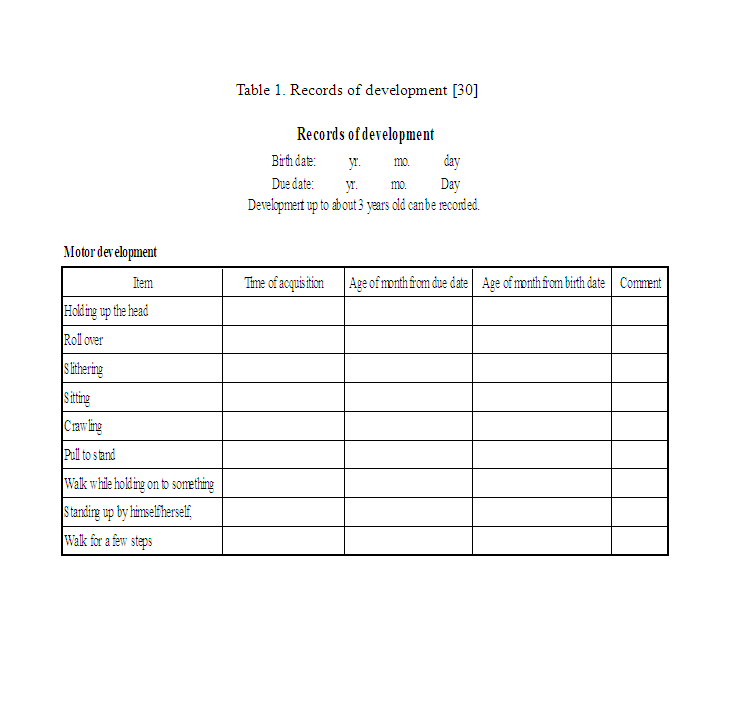

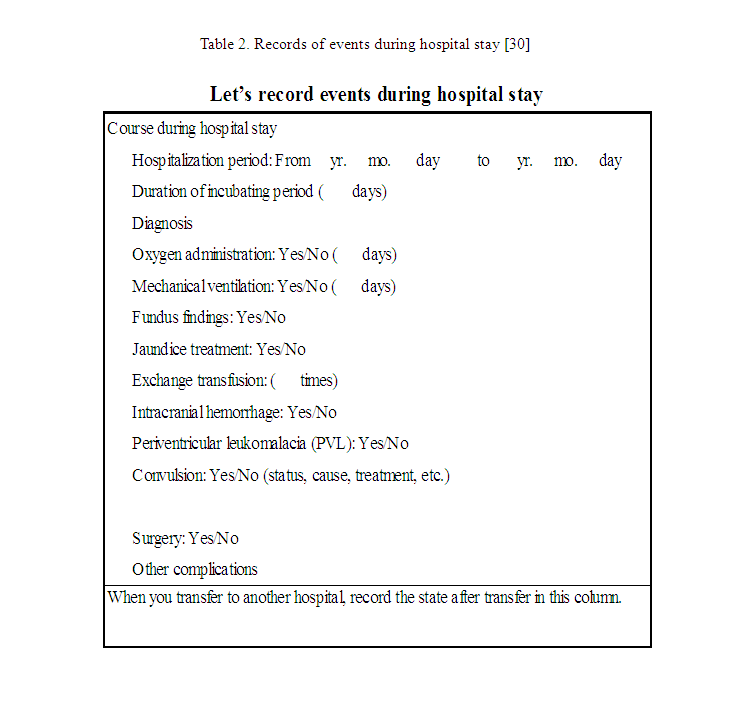

Thus, the course in NICU and state at discharge of low-birth-weight infants cannot be described in Maternal and Child Health Handbook. Moreover, growth and development at a corrected age (age of months from the due date) cannot be recorded in this handbook. Since this handbook does not fit the growth evaluation and child-rearing of low-birth-weight infants in many items, support for low-birth-weight infants and their families cannot be sufficiently guaranteed. In a childcare handbook for mothers of low-birth-weight infants, ‘Little Baby Handbook’ [30], growth curves of extremely low-birth-weight infants are presented by the body weight for evaluation of growth of children (Figure1) [31]. Development items, such as ‘holding up the head’ and ‘roll over’, are listed in a table and the corrected age, age of months from the birth date, and time when the infant could do a development item (year and month) can be entered in each development item(Table 1). Columns for recording the course during staying in NICU and the condition at discharge are also prepared (Table 2).

Figure 1: Growth Curve [30].

Cited from ‘Growth curves of extremely low-birth-weight infants’ (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Motor and Intellectual Disability Research Group) [31]

Note: Nutritional management while staying in NICU has progressed and changed with advances in perinatal medical care. When the current state is compared with that at the time of preparation of the growth curve, nutritional management starting immediately after birth (including the method of intravenous feeding and enriched breast milk) has markedly changed, and if a curve is prepared from current children in the same state, it may surpass this curve. It may be better to pay attention to these points when you evaluate the growth of your child. If you are anxious or have any questions, please ask the physician following your child at the outpatient clinic.

Takeyasu Igarashi (Pediatric Department, Shizuoka City Shizuoka Hospital)

In addition, the handbook contains childcare information from occupational and physical therapists and explanation of diseases (complications) likely to develop in low-birth-weight infants by neonatologists, and a list of sections in charge of maternal and child health in the prefecture as health and medical care information. Furthermore, how to receive vaccination, the subsidy content of and contact addresses for medical expense (infant’s medical expense, medical care for premature babies, rehabilitative treatment, Ministry of Health Research Projects for the Treatment of Specified Chronic Diseases of Infants and for the Treatment of Specified Diseases) and follow-up system for low-birth-weight infants are explained.

Furthermore, messages from mothers of low-birth-weight infants are described in the margin of all pages, and messages from fathers, grandparents, and siblings of low-birth-weight infants and friends are on the last page of the handbook. Advice for rearing twins by persons with experience of rearing twins is also presented.

‘Little Baby Handbook’ complements the mother’s knowledge and insufficiency of public assistance for low-birth-weight infants because it is composed of abundant contents supporting low-birthweight infants and mothers (families). In addition, messages from mothers and families include information on growth, development, and childcare of low-birth-weight infants until school age. These contents reduce the current anxiety of mothers by providing relief and hope through foreseeing child-rearing.

The developmental evaluation of low-birth-weight infants by their mothers based on messages contained in ‘Little Baby Handbook’ may contribute to the early identification of growth retardation and disabilities in these infants. Furthermore, the introduction of rehabilitation facilities through this tool may facilitate early intervention for them. Detailed explanations of maternal and child health administration and support, which encourage mothers to seek early rehabilitation for their children, and empower their parenting, may also serve as a source of maternal support.

However, to my knowledge, no survey has been performed to investigate whether ‘Little Baby Handbook’ leads to improvement of QOL of low-birth-weight infants and their families, reformation of systems for low-birth-weight infants, and improvement of services. In the situation of support for low-birth-weight infant home care lacking preparation of public services, the expectation for the role played by ‘Little Baby Handbook’ is great. To promote support for childcare of low-birth-weight infants at home, evaluation(benefit and problems) of ‘Little Baby Handbook’ by users, mothers of lowbirth-weight infants, is necessary.

The usefulness of ‘Little Baby Handbook’as a measure to provide mental care for the mothers of low-birth-weight infants, promote developmental evaluation by them, and provide informative support for their community lives should be promptly confirmed.It is indispensable for NICU staff to introduce this tool, with an explanation of methods to appropriately use it, in order to promote its utilization among mothers. Evaluation of the tool by multiple professionals is also needed to make it useful for multi-professional collaboration. Thus, for further improvement, ‘Little Baby Handbook’ should be utilized and evaluated by the mothers (families) of low-birth-weight infants, NICU staff, and those involved in community-based medical care and welfare services.

Problems with Home Care of Low birth weight Infants Use of Little Baby Handbook to Support Low birth weight Infants and Families (Mothers) ,

Use of Little Baby Handbook to Support Low birth weight Infants and Families (Mothers) ,

Problems with Home Care of Low birth weight to Support Low birth weight Infants and Families (Mothers),

Use of Little Baby Handbook to Support Low birth weight Problems with Home Care of Low birth weight Infants ,

Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 3 (2018), Article ID: JCNRC-135

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100135Commentary Article

Problems with Home Care of Low-birth-weight Infants: “Use of Little Baby Handbook” to Support Low-birth-weight Infants and Families (Mothers)

Yukiko Tomoyasu*, Ikuko Sobue

Division of Nursing Science, Graduate School of

Biomedical & Health Sciences, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi,

Minami-ku, Hiroshima

734-8553, Japan.

Corresponding Author Details:

Yukiko Tomoyasu, Division of Nursing Science, Graduate School of Biomedical & Health Sciences,

Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8553, Japan.

E-mail: d190391@hiroshima-u.ac.jp

Received date: 11th November, 2018

Accepted date: 06th February, 2019

Published date: 11th February, 2019

Accepted date: 06th February, 2019

Published date: 11th February, 2019

Citation: Tomoyasu Y, Sobue I (2019) Problems with Home Care of Low-birth-weight Infants: “Use of Little Baby Handbook” to

Support Low-birth-weight Infants and Families (Mothers). J Comp Nurs Res Care 4: 135.

Copyright: ©2019, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author

and source are credited

Abstract

Low-birth-weight infants may have various health problems, such as physical growth delay or cerebral palsy, and their mothers may be very anxious or exhausted while rearing them at home. However, public services of the Japanese government for home care of these children and their families are insufficient both in quality and quantity and do not meet their needs. For that reason, 'Little Baby Handbook' was developed for the mothers of low-birth-weight infants. It complements the mother's knowledge and the insufficiency of public assistance for low-birth-weight infants by including information on the growth, development, and childcare of low-birth-weight infants.Keywords: low-birth-weight infant, mother, Maternal and Child Health Handbook

The mothers cannot easily go out because of rearing their infants. They do not have many opportunities to receive peer support and facilities providing respite care are lacking. Although infants require services from many facilities, such as rehabilitation, multidisciplinary cooperation is undeveloped because of undeveloped communitybased integrated care systems and lack of home-visit nursing services for home care infants.

To cope with this situation, ‘Maternal and Child Health Handbook for low-birth-weight infants and their families (mothers)’ was prepared by mothers of low-birth-weight infants and utilized as rearing support for them. In this report, problems with home care of low-birth-weight infants in Japan and ‘Maternal and Child Health Handbook for low-birth-weight infants and their families (mothers)’ are introduced and the benefit of the handbook is discussed.

1. Changes in the estimated number of low-birth-weight infants and national policy for low-birth-weight infants

The number of live births in Japan has steadily decreased since 1975 and it recorded the lowest (976,979) in 2016 [1]. In the composition by birth weight in each sex in 2015, infants with a birth weight lower than 2,500 g accounted for 8.4 and 10.6% of boys and girls, respectively, showing a nearly 2-fold increase from those (4.8 and 5.6%, respectively) in 1980. In a survey performed by the Japan Pediatric Society Neonatal Committee, the mortality rate of neonates with a very low birth weight of 1,000 g or higher decreased from 20.7% in 1980 to 3.8% in 2000, and that of neonates with a birth weight of 500 g or higher decreased from 55.3 to 15.2%. The mortality rate of neonates with a birth weight lower than 500 g also decreased from 91.2% in 1985 to 62.7% in 2000 [2,3]. Progress in neonatal medical care, such as introduction of artificial ventilation therapy and artificial pulmonary surfactant replacement therapy for preterm infants with respiratory disorder, improvement of pregnancy and delivery management, and progress in regional arrangement of perinatal medical care system after the latter half of the 1970s contributed to the reduction of the neonatal mortality rate.However, not all life-saved infants achieve sequela-free survival and many infants require continuation of medical care [4]. Insufficiency of beds in NICU due to an increase in infants hospitalized in NICU for a prolonged period caused not only difficult acceptance of neonates but also social problems, such as rejection of admission of the mothers [5]. To cope with these problems, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare specified the proper number of beds in NICU to 25-30 per 10,000 births in the Guidelines for the Establishment of Perinatal Care Systems in 2010, and promotes preparation of NICU and environments facilitating rehabilitation and medical care of home care infants according to the actual regional situations [6].

According to the nationwide estimate in 2012, about 150 infants were discharged with ventilator attachment in the year and this number is about 5 times of that (33.6) in 2004 [7]. Of ventilatorattached infants discharged within one year after admission to NICU, 46% were discharged to home, 33% and 19% transferred to internal and external pediatric wards, respectively, and 67% of them finally transferred to home care.

2. Health problems of low-birth-weight infants

Low-birth-weight infants have problems with delayed growth, outcome of development, handicaps, such as cerebral palsy and intellectual disability, and requirement of medical care in severe cases.The growth values are low in many very low-birth-weight infants even when compared with those at the corrected age. The growth catch-up rate (increase exceeding -2SD or 2.3 percentile of infantile physical growth value) of low-birth-weight infants decreases with shortening of the period of gestation [8]. The height and body weight of infants with a birth weight lower than 750 g cannot catch up at 3 years old [9,10]. The chronological age at which they exceed the 10th percentile of the infantile physical growth value is 5 years old for the body weight and 4 and 5 years old for the height in boys and girls, respectively.

In a longitudinal survey of long-term outcomes of very low-birthweight infants (below 1,000 g), the frequency of cerebral palsy at 6 years old was 17.3% in children born in 2000 [11], whereas it was 15.5% in a survey of 6-year-old children in 1995 [12], showing a slight increase in children with cerebral palsy. The frequency of intellectual developmental disorder (70 < Intelligence Quotient)at 6 years old was 26.6% and that including the boundary zone (70 < Intelligence Quotient < 85)was 42.6%. Children with intellectual developmental disorder including the boundary zone significantly increased at 6 years old compared with that (33.2%) at 3 years old. Development of very low-birth-weight infants with no neurological disorder is still lower than the average of healthy children. For example, on an analytical infantile development test using Enjoji’s development scale, the development of low-birth-weight infants from 1 to 2 years old was below the average of healthy infants. Language understanding of low-birth-weight infants catches up with development of the corresponding age at 3 years old, but speech is still below average at 3 years old [13].

The outcome of low-birth-weight infants includes problems with severe motor and intellectual disabilities. Severe physical disability and severe intellectual disability overlap in this condition [14]. This term is used for child welfare-based administrative measures and defined as a condition with ADL up to sitting and IQ below 35 in the judgment criteria employing Oshima’s classification [15]. Infants constantly requiring medical management have rapidly increased with rapid progress in perinatal and infant medical care in Japan, although they do not meet the definition of severe motor and intellectual disabilities. Severe motor and intellectual disabilities and the necessity of constant medical care are combined in these infants and they are defined as ‘children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities, medical care dependent group (SMID-MCDG)’. Using the score of SMID-MCDG (respirator management: 10, IVH: 10, nasopharyngeal airway: 5) established by Suzuki et al. [16], infants scored 25 or higher are judged as ‘SMID-MCDG’ and those scored 10 or higher are judged as ‘sub-SMID-MCDG’ [17].

The onset time of medical care-dependent severe motor and intellectual disabilities is in the neonatal period in 67%. According to the 2007 complete enumeration inventory surveyof SMID-MCDG (nationwide 8 prefectures), 444 were SMID-MCDG and 649 were semi-SMID-MCD [18]. Medical care performed at home in 747 SMID-MCDG/semi-SMID-MCDG is as follows: tube feeding in 702 (94%), postural change in 486 (65%), tracheotomy in 354 (47%), ventilator in 171 (23%), frequent suctioning in 194 (26%), and oxygen administration in 216 (29%).

3. Support for low-birth-weight infants and mothers

Mothers of low-birth-weight infants have mental health problems with self-dispraise for giving birth to their low-birth-weight infants and mother-infant separation [19,20] and anxiety for growth and development of their children. A survey on rearing very low-birthweight infants clarified that the parents of 384 families (75%) were anxious about physical growth and development of their children and their anxiety was strong during hospitalization of the child and early after discharge [21]. Since low-birth-weight infants have problems with the motor function, intellectual development, and behavior at a high rate, their mothers have difficulty in appropriately responding to various reactions of their children [22], which strengthens negative emotions to their infants and increases child-rearing anxiety and stress [23]. Moreover, mothers have problems with rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy and intellectual disability and those requiring medical care.In a survey performed by Sugimoto et al. in 2007, 70% of SMID-MCDG received home care, and home-visiting nursing care station and home help service were used by 18 and 12%, respectively. Regional welfare service was not frequently used and the family mostly carries out care. The mothers mainly perform home care of SMID-MCDG, bearing a large burden. Especially, they have insomnia and chronic fatigue immediately after initiation of home care life [24] because they cannot judge the child’s symptoms and perform home care while being afraid of life crisis [25]. Moreover, the mothers require a lot of time and effort for various applications necessary for home care of infants: Applications for public expense for medical care, physically disabled persons’ certificate, and Special Child Rearing Allowance, investigation of and application for medical devices and welfare equipment for home care, and application for home modification.

The needs for rehabilitation and respite care are high in children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities and those requiring and medical care. However, utilizable social resources are lacking and social support does not catch up with the needs. In 2013, the Advisory Council on Social Security Medical Care Committee [26] proposed construction of medical care and welfare service systems necessary for home care of infants who required long-term medical treatment in NICU [27]. In 2015, the Act for Comprehensive Welfare for Persons with Disabilities proposed detailed measures for the diverse needs of children with disabilities. In 2016, the Act for Comprehensive Welfare for Persons with Disabilities and Child Welfare Act clearly stipulated children with medical care as ‘children with disabilities requiring long-term medical care’, and set the obligation of local governments to make efforts to prepare a system for liaison and coordination with institutions providing support of related fields, such as health and medical care and welfare, for these children to smoothly receive necessary support, in consideration of burdens on their families [28]. However, unlike long-term care insurance and community-based integrated care systems for adults, no common framework connecting medical care and welfare is available for pediatric home care. Accordingly, multidisciplinary cooperation is lacking and the mothers have to inevitably function as a key person to connect many facilities.

4. Necessity of Maternal and Child Health Handbook for lowbirth-weight infants

The bases of maternal and child health measures in Japan are Maternal and Child Health Handbook and baby health checkups. The greatest significance of Maternal and Child Health Handbook is that information concerning maternal and child health from pregnancy to delivery and infancy can be managed with one handbook. Maternal and Child Health Handbook serves as a tool to continuously assure maternal and child health services performed by various professions at diverse time-points and scenes [29]. Maternal and Child Health Handbook contains evaluation of development of term infants and child care information corresponding to the growth of term infants. The entry column for the time-point of discharge is prepared for term infants.Thus, the course in NICU and state at discharge of low-birth-weight infants cannot be described in Maternal and Child Health Handbook. Moreover, growth and development at a corrected age (age of months from the due date) cannot be recorded in this handbook. Since this handbook does not fit the growth evaluation and child-rearing of low-birth-weight infants in many items, support for low-birth-weight infants and their families cannot be sufficiently guaranteed. In a childcare handbook for mothers of low-birth-weight infants, ‘Little Baby Handbook’ [30], growth curves of extremely low-birth-weight infants are presented by the body weight for evaluation of growth of children (Figure1) [31]. Development items, such as ‘holding up the head’ and ‘roll over’, are listed in a table and the corrected age, age of months from the birth date, and time when the infant could do a development item (year and month) can be entered in each development item(Table 1). Columns for recording the course during staying in NICU and the condition at discharge are also prepared (Table 2).

Figure 1: Growth Curve [30].

Cited from ‘Growth curves of extremely low-birth-weight infants’ (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Motor and Intellectual Disability Research Group) [31]

Legend of Figure 1.

Growth curve of extremely low-birth-weight infants

This growth curve was prepared in 1994 by the former Ministry of Health and Welfare Motor and Intellectual Disability Research Group. This was prepared based on the growth of children with no obvious neurological abnormality at a corrected age of one year and 6 months (counted from the due date, not from the birth date) in babies born with a birth weight lower than 1,500 g at 54 facilities nationwide, i.e., children with relatively smooth growth. Before this curve was published, no criteria for the evaluation of preterm infants with a low birth weight were available, and mothers often uttered a sigh looking at the curve of their own child being constantly lower than the growth curve of term infants as presented in the Maternal and Child Health Handbook. There is large individual variation in growth due to factors including parents’ physiques and child’s physical constitution, such as growth speed. So, the curve only represents the standard. It may be better to refer to changes in the curve not based on the value at one point. If changes in the growth of your child largely exceeds this curve, you can fill in the normal infant growth curve in the Maternal and Child Health Handbook.Note: Nutritional management while staying in NICU has progressed and changed with advances in perinatal medical care. When the current state is compared with that at the time of preparation of the growth curve, nutritional management starting immediately after birth (including the method of intravenous feeding and enriched breast milk) has markedly changed, and if a curve is prepared from current children in the same state, it may surpass this curve. It may be better to pay attention to these points when you evaluate the growth of your child. If you are anxious or have any questions, please ask the physician following your child at the outpatient clinic.

Takeyasu Igarashi (Pediatric Department, Shizuoka City Shizuoka Hospital)

In addition, the handbook contains childcare information from occupational and physical therapists and explanation of diseases (complications) likely to develop in low-birth-weight infants by neonatologists, and a list of sections in charge of maternal and child health in the prefecture as health and medical care information. Furthermore, how to receive vaccination, the subsidy content of and contact addresses for medical expense (infant’s medical expense, medical care for premature babies, rehabilitative treatment, Ministry of Health Research Projects for the Treatment of Specified Chronic Diseases of Infants and for the Treatment of Specified Diseases) and follow-up system for low-birth-weight infants are explained.

Furthermore, messages from mothers of low-birth-weight infants are described in the margin of all pages, and messages from fathers, grandparents, and siblings of low-birth-weight infants and friends are on the last page of the handbook. Advice for rearing twins by persons with experience of rearing twins is also presented.

‘Little Baby Handbook’ complements the mother’s knowledge and insufficiency of public assistance for low-birth-weight infants because it is composed of abundant contents supporting low-birthweight infants and mothers (families). In addition, messages from mothers and families include information on growth, development, and childcare of low-birth-weight infants until school age. These contents reduce the current anxiety of mothers by providing relief and hope through foreseeing child-rearing.

The developmental evaluation of low-birth-weight infants by their mothers based on messages contained in ‘Little Baby Handbook’ may contribute to the early identification of growth retardation and disabilities in these infants. Furthermore, the introduction of rehabilitation facilities through this tool may facilitate early intervention for them. Detailed explanations of maternal and child health administration and support, which encourage mothers to seek early rehabilitation for their children, and empower their parenting, may also serve as a source of maternal support.

However, to my knowledge, no survey has been performed to investigate whether ‘Little Baby Handbook’ leads to improvement of QOL of low-birth-weight infants and their families, reformation of systems for low-birth-weight infants, and improvement of services. In the situation of support for low-birth-weight infant home care lacking preparation of public services, the expectation for the role played by ‘Little Baby Handbook’ is great. To promote support for childcare of low-birth-weight infants at home, evaluation(benefit and problems) of ‘Little Baby Handbook’ by users, mothers of lowbirth-weight infants, is necessary.

The usefulness of ‘Little Baby Handbook’as a measure to provide mental care for the mothers of low-birth-weight infants, promote developmental evaluation by them, and provide informative support for their community lives should be promptly confirmed.It is indispensable for NICU staff to introduce this tool, with an explanation of methods to appropriately use it, in order to promote its utilization among mothers. Evaluation of the tool by multiple professionals is also needed to make it useful for multi-professional collaboration. Thus, for further improvement, ‘Little Baby Handbook’ should be utilized and evaluated by the mothers (families) of low-birth-weight infants, NICU staff, and those involved in community-based medical care and welfare services.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors have no conflicting interest in this studyAuthor Contributions

TY and SI were involved in all the process of this study from the conception of this study to drafting and final approval of the manuscript.References

- Health, Labour and Welfare Statistics Association (2017)

National health trend 2017/2018. J Health Welfare Stat 64: 9

59-62.

- Mishina J (2006) Long-term outcome of very low birth infant.

Acta Obstet Gynaecol Jpn 58: 127-131.

-

Horiuchi T, Itani Y, Ohno T, Katsube K, Nakamura T, et al.

(2002) Studies on the states of care for high risk neonates (2001)

and neonatal mortality (2000)in our country. J Jpn Pediatr Soc

106: 603-613.

- Iida K (2013) Current status of NICU: Home care starting from

NICU (Feature on pediatric home care starting from NICU).

Perinatal Med 43: 1331-1333.

- Maeda H (2015) Current status and issues of pediatric home

care. The Jpn Acad Home Care Physician16: 176-183.

- Ministry of Health, Labour Welfare. The Guidelines for the

Establishment of Perinatal Care Systems.View

- Tamura M, Matsumoto Y (2016) Current status and issues of

pediatric home care and solutions: Measures taken in Saitama

Prefecture. J Child Health 75: 964-700.

- Kono Y (2016) Physical development of low-birth-weight

infants. Perinatal Med 46: 908-910.

- Kato N, Okuno A, Takaishi M (2001) Results of survey on infant

physical development in 2000. J Child Health 60: 707-720.

- Kusuda S (2013) Growth and development of low-birth-weight

infants and preterm infants. Matern & Child Health 653: 4-5.

- Uetani Y (2010) Results of national data collection of 6-year

outcome of extremely low-birth-weight infants born in 2000 and

3-year outcome of those born in 2005. MHLM grants report for

FY 2007-2009: Comprehensive Research Project for Families

and Children 71-79.

- Nakamura H, Uetani Y (2003) Results of national data collection

of 6-year outcome of extremely low-birth-weight infants born in

1995. MHLM grants report for FY 2002: 324-330.

- Mukasa A, Yamagami T (2006) Developmental characteristics

of extremely low birth weight infants. Kurume Univ Psychol

Res 5: 63-74.

- Social Welfare Foundations, Nationwide Association for

Children (Persons) with Severe Physical and Intellectual

Disabilities.View

- Oshima K (1971) Basic issue on severe motor and intellectual

disabilities. Jpn J Public Health 35: 648–655.

- Suzuki Y, Tatsuno M, Yamada M (1995) Seriously handicapped

children with intensive medical cares - Definition and problems.

J Child Health 54: 460-410.

- Suzuki Y, Takei S, Takechi N, Yamada M, Morooka M, et al

(2008) New scoring system for patients with severe motor and

intellectual disabilities, medical care dependent group. J Severe

Motor Intellect Disabil 33: 303–309.

- Sugimoto T, Kawahara N, Tanaka H, Tanizawa T, Tanabe I et

al (2007) Current status and issues of medical care for medical

care-dependent children with severe motor and intellectual

disabilities: Questionnaire survey in nationwide 8 prefectures.

J Jpn Pediatr Soc. J Jpn Pediatr Soc 112: 94-101.

- Nagata M, Nagai Y, Sobajima H, Ando T, Honjo S et al. (2003)

Depression in the mother and maternal attachment-Results from

a follow-up study at 1 year postpartum. Psychopathology 36:

142-151.

View

- Sandra J, Weiss SJ, Chen JL (2002) Factors influencing maternal

mental health and family functioning during the low birthweight

infant’s first year of life J Pediatr Nurs 17: 114-125.

View

- Nakamura H (1996) Survey on childcare of extremely low-birthweight infants. MHLM grants report for FY 1996, Research on

motor and intellectual disabilities; Study on perinatal medical

care system and information management. 73-75.

- Hayashida K, Nakatsuka M (2014) Promoting factors

of physical and mental development in early infancy: A

comparison of preterm delivery/low birth weight infants and

term infants. Environ Health Prev Med 19: 160-171.View

- Baía I, Amorim M, Silva S, Kelly-Irving M, de Freitas C et al.

(2016) Parenting very preterm infants and stress in Neonatal

Intensive Care Units. Early Hum Dev 101: 3-9.View

- Kusano J (2016) A literature review regarding skill acquisition

among mothers of children requiring medical care at home. Jpn

J Matern Health 57: 447-456.

- Ichihara M, Shimono J, Sekito Y (2016) Family management

of a family living with a child who has profound multiple

disabilities and is medically dependent at home - Coping

behaviors dealing with family difficulties faced in daily life -.

Acta Obstet Gynaecol Jpn 9: 99-107.

- The 37th Meeting of the Advisory Council on Social Security

Medical Care Committee, Ministry of Health, Labour Welfare

(2013) Opinions Concerning the Medical Care Act and

Amendment (draft).View

- Sakamoto S (2016) Expectations for CNSs, NPs and Visiting

Nurses in home-based care for children. J Jpn Soc Child Health

Nurs 25: 125-128.

- Health, Labour and Welfare Statistics Association (2017) Trend

of national welfare and nursing 2017/2018. J Health Welfare

Stat 64: 116-143.

- Misawa A (2013) Current status and problems of maternal and

child health.J Kyoto PrefUniv Med 122: 687-695.

- Kobayashi S (2011) Little Baby Handbook(1st ed) Meiyusha

CoLtd, Shizuoka, Japan.

- Itabashi K (1992) Making of the postnatal growth curve

of extremely immature infant. The growth from the NICU

hospitalization to 5 years old. (An allotment study, Study on

management of the high-risk child), 1992 Public welfare mind

and body study. Study on general care system of the high-risk

child 96-106.

Problems with Home Care of Low birth weight Infants Use of Little Baby Handbook to Support Low birth weight Infants and Families (Mothers) ,

Use of Little Baby Handbook to Support Low birth weight Infants and Families (Mothers) ,

Problems with Home Care of Low birth weight to Support Low birth weight Infants and Families (Mothers),

Use of Little Baby Handbook to Support Low birth weight Problems with Home Care of Low birth weight Infants ,

Comments

Post a Comment