Integrating Nursing Education in Students’ Extracurricular Activities: Students’ Motivations and Benefits

https://gexinonline.com/archive/journal-of-comprehensive-nursing-research-and-care/JCNRC-133

Materials and Methods: The International Nursing Students Association (INSA) organized a health screening targeted towards minority populations at the 2017 Asian Festival. Students were provided with orientation and practice to conduct the screening. They were also given a chance to experience the many activities of the festival. Following the screening, the student volunteers (N=12) were surveyed to identify motivators for CSL participation; completed a survey for health screening skills and transcultural competencies before and after the event; and wrote a 6-word reflection. Quantitative data were statistically analyzed; qualitative data were analyzed for emerging themes.

Results: The predominantly female minority students (83%) joined the CSL activity for personal improvement (50%), commitment to the community (33%), and professional improvement (16%). They had significant (p<0.05) improvement in clinical skills and transcultural competencies. Reflection themes were congruent with the development of clinical skills, contribution to community health promotion, and cultural appreciation.

Conclusions: This extracurricular CSL activity improved nursing skills, transcultural competencies, community health promotion, and cultural appreciation. Knowledge of motivators can develop strategies to enhance student participation. Extracurricular CSL activities could be an avenue to integrate nursing education into real-world experiences, providing care for diverse populations.

Keywords: community service learning, undergraduate nursing students, benefits, motivators, student organization

Schools of higher education can implement practices that promote educationally purposeful extracurricular activities within the context of their campus communities. The educational preparation of health care professionals can influence the development of cultural proficiency among future health care providers. Health professions education has been considered as a critical and potentially most effective intervention to eliminate health care disparities [4]. Community service learning (CSL) is a tool that can be utilized to connect academic content learned by students to community-based projects to improve learning outcomes [5]. Service learning is a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities [6]. CSL is a valuable learning tool and an effective strategy for engaging students. CSL activities provide opportunities for the student to work and serve the community and expose the students to the realities of health promotion and disease prevention [4,7-8].

Outside of the classroom, students can also be engaged in CSL activities through student organizations, providing them with more opportunities to be involved with the community.

Participation in minority organized events allows for unique immersive cultural encounters that are essential for learning about cultural diversity and health disparity issues. Exposure to a diverse population and serving in an authentic environment can provide opportunities for students to understand the holistic and inclusive nature of cultural events, which can contribute to their academic learning and enhancement of their personal and social d evelopment [4,7-9]. In addition to enhancing and reinforcing academic education, personal and interpersonal development, as well as community engagement, has also been identified as significant benefits of participating in CSL activities [9-11]. However, despite these documented positive effects of CSL, student participation in extracurricular CSL activities organized by student organizations is not well documented. It is not known what motivates students to participate in these activities. The International Nursing Students Association (INSA) of the University of Texas Health at San Antonio, in its eight years of existence, have consistently organized 2-4 CSL health screenings per year during community events held by or for minority populations. Participation in these events by nursing students is relatively poor. Knowledge of students' motivating factors and perceived benefits regarding extracurricular CSL projects may improve student involvement, and inform the planning of these events. According to Cone and Harris’ Six Stage Lens theoretical model for service learning, individual, interpersonal, and social-cultural aspects influence the nature of CSL [7]. The student’s value system, individual characteristics, and past experiences may motivate participation in the CSL activity. The type of preparation, mentorship, and characteristics of CSL activity would influence the benefits of the CSL experience. Hence, this evaluative study aims to determine the nursing students' motivating factors and perceived benefits from participating in an extracurricular CSL activity at an Asian Festival.

For this project, INSA organized the free health screening for the 2017 Asian Festival in collaboration with the Institute of Texan Cultures (ITC) on February 4, 2017. The ITC hosts the annual Asian Festival in San Antonio, Texas to celebrate and showcase the unique cultures and traditions of the Asian community [13]. Advertisements for health screening student volunteers were sent out via student cohort Facebook pages and through the school-wide e-mail distribution list to potentially reach all of the 757 enrolled students (undergraduate students = 533; graduate students = 224) for the Spring 2017 semester.

The health screening was held from 10 am to 3 pm, and was open to all attendees of the festival. Undergraduate BSN students (N=17) volunteered to conduct the health screening which consisted of obtaining the health history, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and blood glucose determination. Appropriate health education from the health history and health screening results were provided to all festival attendees along with tools to improve health literacy using "Ask Me 3™" [14,15] and to detect signs of stroke [16]. Ask Me 3™ is an educational program that encourages patients and families to ask three specific questions to their healthcare providers: 1) What is my main problem? 2) What do I need to do? 3) Why is it important for me to do this? [15]. Studies have shown that patients who use the Ask Me 3™ tool had improved patient-provider communication; the tool empowered the patients to ask questions to help them understand better their health condition [14,15]

Before the event, an orientation session was held to inform student volunteers of the health screening activities and their respective roles and responsibilities. The screening included three stations: station 1- health history and BMI determination; station 2- blood pressure and blood glucose screenings; and station 3- health education (including the provision of Ask Me 3™ and stroke sign tools). All volunteers were initially allowed to choose a station and were encouraged to rotate between stations which provided an opportunity for the students to practice a variety of skills.

Following the CSL event, the volunteers were asked to complete an anonymous survey that included demographic information (i.e., gender, age, and ethnicity), their nursing program (i.e., traditional track or accelerated track), graduate specialty (if they are in graduate school), semester level, and previous CSL experience. The survey also asked the volunteers to identify their primary motivation for participating in the CSL activity, with options including personal improvement (learning new things/ideas/culture), professional improvement (course requirement/include activity in resume), commitment to organization (show active participation to organization’s activity,) commitment to community (sense of “giving back”/community service), cultural curiosity/awareness and understanding (experience the community), curiosity (“What is this all about?”), or others (which the volunteers were asked to indicate). Additionally, the students were asked to rate, using 0-5 Likert-type scale (where 0=N/A, 1=poor to 5=highest), their health screening skills (i.e., health history and assessment, blood pressure, and blood glucose) and transcultural competencies (i.e., knowledge, understanding, communication, and proficiency). Finally, the student volunteers were asked to compose a 6-word reflection story [17] based on their experience from the CSL activity [18].

For the 6-word story reflections, a two-author team initially analyzed the stories for emerging central themes. Components of each story were then re-analyzed for categorization and discussed at length to reach concordance among theam members. Identified emerging themes were shown to the third author for confirmation. Other issues related to trustworthiness such as credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability were achieved through sharing the results, interpretations, and conclusions to some volunteer student participants. The 6-word stories were then entered into Wordle [19], a program that generates word clouds based on the text provided. The visual word cloud created showcases the prominence of the most frequent words used.

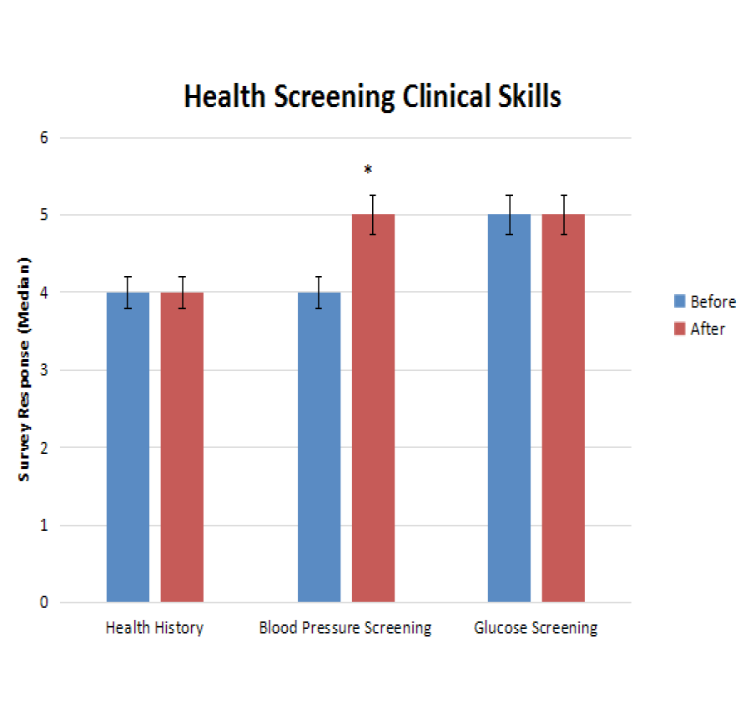

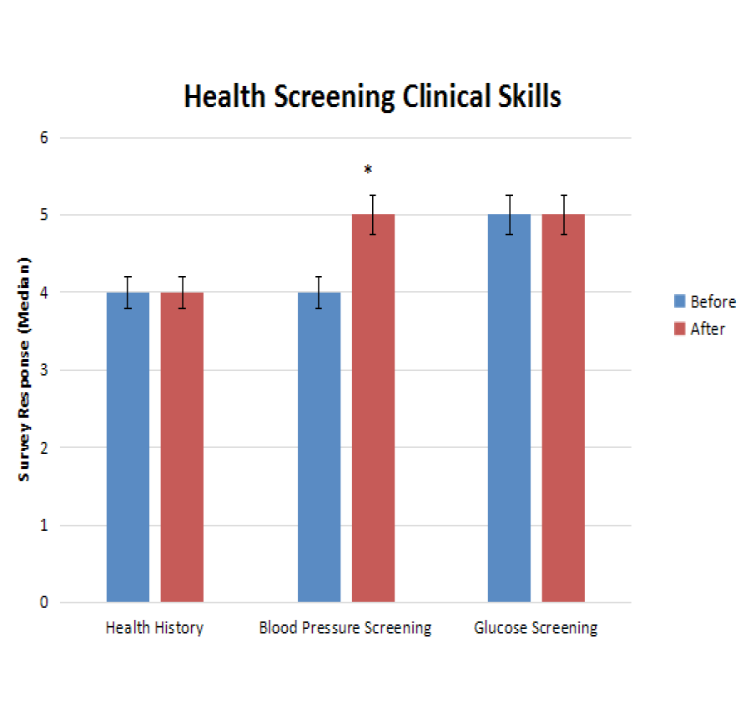

Figure 2: Student volunteers’ response regarding their health screening skills before and after the activity. *p<0.05 using Mann-Whitney test to compare before and after scores.

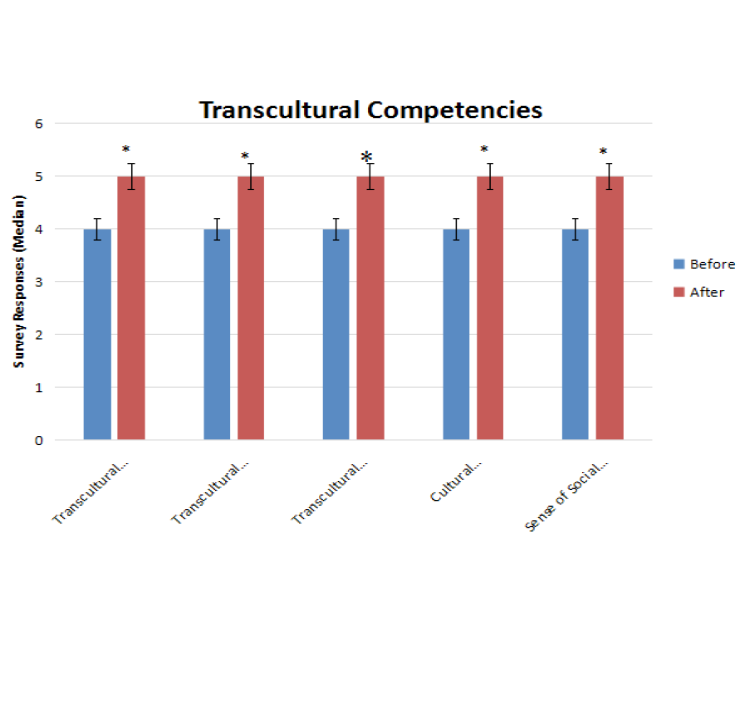

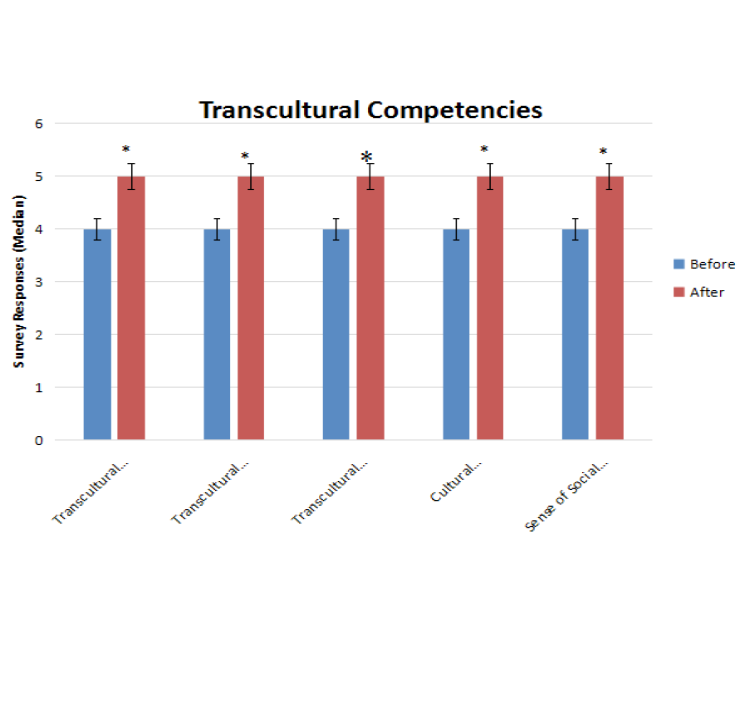

Figure 3: Student volunteers’ survey response regarding their transcultural competency skills before and after the activity. *p<0.05 using Mann-Whitney test to compare before and after scores.

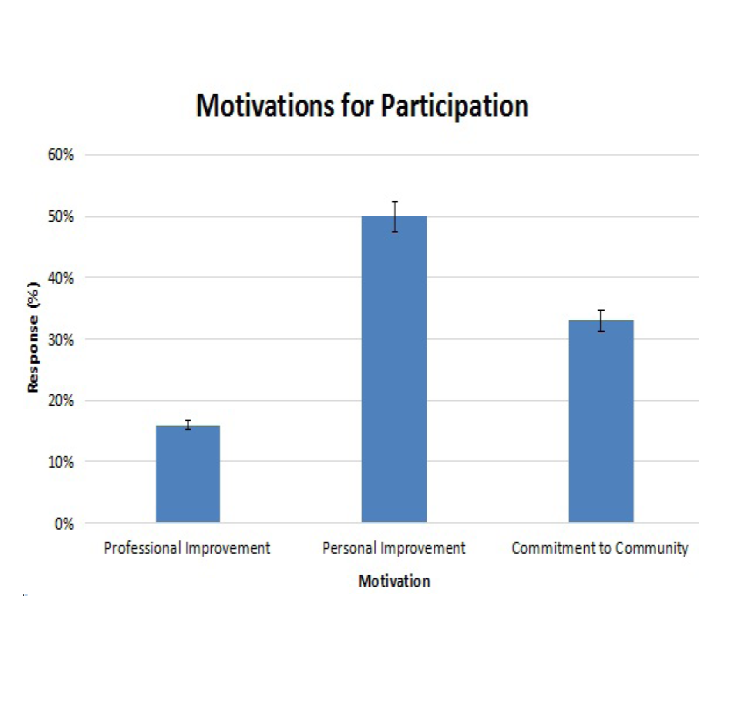

Personal improvement is the primary motivator for this group of undergraduate nursing students to participate in this extracurricular CSL activity. In the survey, personal improvement was described as learning new things, ideas, or culture. The second strongest motivator is the commitment to the community, described as a sense of "giving back" or community service. These results are congruent with other studies that found internal factors (i.e., altruism, duty, self-expansion) to be the strongest motivators for students to participate in community service [20-23]. However, all of these studies were among college students, but not nursing; and the CSL activities were part of the graded curriculum. This study identified critical motivators for nursing undergraduate students to participate in a purely extracurricular activity, i.e., with no grades. There is minimal literature on this topic. Lapiz-Bluhm and Woosley [7] reported that undergraduate nursing students are motivated to participate in extracurricular activities mainly due to professional improvement (23%), personal improvement (21%), and commitment to organization (15%), commitment to community (18%), cultural awareness (11%) and curiosity (9%) [7]. The difference in results may be accounted for in terms of the difference in ages between the two populations where the current study has a younger demographic (range= 19-34 vs. 19-42 years of age), size of the sample (12 vs. 32), previous CSL experience (8 vs. 18), and ethnicity composition [7].

Darby and colleagues [24] found that college students become more motivated to partake in community service when "they enjoy their experience, have an interest in helping people… and feel a sense of responsibility to the community." Another study found that high school students that continued to partake in community service activities in college were driven by internal factors [22]. Personal and emotional investments in the community encourage students to serve the people in these communities. Thus, students' exposure to various activities would help them form relationships with community partners and its members. Student-led organizations, such as INSA, is one way to help students connect with various community partners through extracurricular CSL activities. Jones and Hill [22] found that visibility and accessibility of community service opportunities influenced student participation. Ferrari & Bristow [21], in their survey of psychology students, found that altruistic campus atmosphere predicted the students' motivations for community service involvement. Being a part of specific programs and activities, such as fraternities/sororities are also an effective influence on the students' involvement in community service [22,23]. This study also found the commitment to the community to be the second most frequent motivator for nursing students. The current results are different from other studies that determine involvement through club or classes and learning new experience to be the second most frequent motivators [23]. Being mindful of the motivating factors behind CSL involvement by students may help student leaders, faculty, and community partners in planning community service events to increase student participation. Student-led organizations and faculty can organize activities tailored to the interests of the students that would entice them to partake in CSL events.

Although there was a general pattern of increasing scores post-CSL activity regarding the student volunteers' clinical skills, the increase was not significant except for blood pressure screening skills. This result is in contrast to Lapiz-Bluhm and Woosley’s [7] previous findings of a significant increase in self-reported scores of first-time student volunteers' clinical skills (i.e., including health history, blood pressure, and blood glucose determination) after participating in CSL activity. It is worth noting that there was not a significant difference in the self-reported scores of experienced student volunteers. The lack of statistical difference for the glucose screening skill scores may be due to the ceiling effect; the students already rated themselves high at baseline. Nevertheless, this current study’s result suggests that participating in a short-term extracurricular CSL activity can help improve nursing students' blood pressure taking skills. These outcomes reflect the students' perceived benefits of the CSL activity in regards to their clinical skills. CSL activities, such as a health screening, not only help nursing students practice their learned skill in a clinical setting, it is a way for them to connect theory and translate them into practice, thus improving learning outcomes. This is similar to other studies that found service learning increased retention of academic contents and increased learning outcomes by helping them see the connection between theory learned in the classroom setting and the clinical work [10,24-27]. CSL activities provide opportunities for nursing students to practice various clinical skills which could help them become even more proficient in these areas.

Similar to the clinical skills scores, there was a tendency for the transcultural competency scores to increase after the health screening. However, only the transcultural knowledge and transcultural communication reached statistical significance. The nature of the CSL activity may have influenced this result. The activities involved in the health screening encouraged the students to communicate and interact with the attendees of the festival throughout the event—from the intake, where the students took the health history of the festival attendees, to the last station where they provided health education. Erickson [28] found that students reported improvement in the communication skills after participating in a service learning project in a non-clinical setting. This result is similar to a previous study by Lapiz-Bluhm and Woosley [7] where they found that both first-time and experienced volunteers reported a significant increase in transcultural knowledge and communication. There was no statistical difference in transcultural understanding and cultural proficiency scores. Failure to reach statistical significance may be because the student volunteers were not given sufficient time with the community. The health screening only lasted for a few hours which may not be adequate time to improve cultural understanding and cultural proficiency. The study’s result is different from other studies that found participating in service learning courses can increase cultural competency and understanding [7,28,29]. The difference in the results may be accounted to the nature of the interventions. The previous studies were conducted using semester-long courses, whereas this study looked at the effects on cultural competencies after one event. The scores for sense of social justice also failed to reach statistical significance. This finding is different from previous studies that showed improvement in civic engagement scores after a service learning course [9,30]. Nokes and colleagues [31] found that civic engagement scores of college students increased after participation in a service learning activity. Groh et al. [30] saw an overall increase in leadership and social justice skills of nursing students following service. Watts et al. [32], in their study of oncology health providers caring for minorities, found that the health providers felt uncertainty and discomfort when caring for minority populations—with cultural and language barriers as some of the main issues. Thus, it is essential that healthcare providers receive training and education tailored to developing cultural awareness and proficiency [32]. Organizing more minority-centered extracurricular CSL activities can provide the students with more opportunities to interact with the minority populations, and help them further improve their transcultural skills and sense of social justice. CSL activities centered on minority populations, such as an Asian Festival, allow students to work in an authentic and immersive environment where they can develop an appreciation of the community they are serving and its cultural background. It can also be a way to introduce nursing students to various cultural values and beliefs, thus helping them develop cultural awareness and help them further enhance their cultural proficiency.

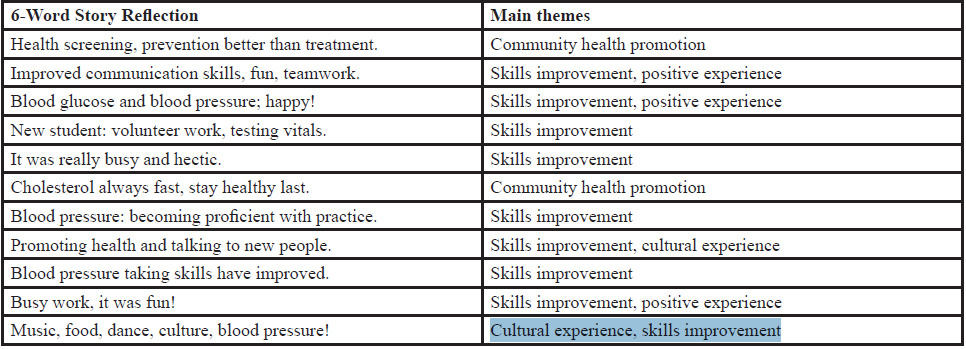

Finally, the students were asked to write a six-word story to reflect on their experience after the health screening. Six-word stories are often attributed to Ernest Hemingway, having been credited for writing "For sale: baby shoes, never worn" [19]. Influenced by the literary legend, Smith magazine founded the Six-word Memoir Project in November 2006 and had since gained prominence in the popular culture [33]. This practice has since found its way in the classroom setting [17,34]. Creating a six-word story is a simple and creative way for students to reflect on their experience. It is important that students critically reflect on their experience as it helps them connect what happens in the community and the academic setting [35]. It is essential for them to internalize their commitment to serving others. The six-word stories written by the student volunteers were inputted into Wordle, a visual cloud generator, to analyze recurring themes. Wordle is a program that produces visual word clouds that showcases the most frequently used words [19]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on CSL reflections to utilize Wordle. More importantly, the word cloud generated revealed themes that were congruent with the results of the survey—with the most frequently used words being "blood pressure," "improved," and “fun." The themes suggest that the students believe they have improved after the CSL activity while having fun doing so.

Integrating Nursing Education in Students’ Extracurricular Activities: Students’ Motivations and Benefits ,

Integrating Nursing Education in Students Extracurricular Activities Students Motivations and Benefits ,

Integrating Nursing Education Students Extracurricular Activities Students Motivations ,

Students Motivations and Benefits Integrating Nursing Education Students Extracurricular Activities ,

Extracurricular Activities Integrating Nursing Education Students Students Motivations and Benefits ,

Integrating Nursing Education in Students Extracurricular Activities ,

Students Motivations and Benefits Integrating Nursing Education in Students Extracurricular Activities ,

Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 3 (2018), Article ID: JCNRC-133

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100133Research Article

Integrating Nursing Education in Students’ Extracurricular Activities: Students’ Motivations and Benefits

Ma. Kathrina Claudine Calilung, M. Danet Lapiz-Bluhm*

1School of Nursing, University of Texas

Health Science Center at San Antonio 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio,

TX 78229-3900, USA.

Corresponding Author Details:

M. Danet Lapiz-Bluhm, School of Nursing, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio TX 78229-3900, Telephone: +1-210-567-5790, USA.

E-mail: lapiz@uthscsa.edu

Received date: 04th September, 2018

Accepted date: 15th January, 2019

Published date: 30th January, 2019

Accepted date: 15th January, 2019

Published date: 30th January, 2019

Citation: Calilung MKC, Lapiz-Bluhm MD (2019)

Integrating Nursing Education in Students’ Extracurricular Activities:

Students’ Motivations and Benefits. J Comp Nurs Res Care 4: 133.

Copyright: ©2019, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author

and source are credited

Abstract

Introduction: Schools of higher education can implement practices that promote educationally purposeful extracurricular activities within the context of their campus communities. Community service learning (CSL) activities have traditionally been used in nursing programs as graded course activities, usually in community health nursing courses. Student organizations can be instrumental in providing extracurricular ungraded opportunities for students to do CSL. This paper describes the conduct of an extracurricular CSL activity through a student organization which integrated nursing education competencies. Moreover, it determines the motivations and perceived benefits of extracurricular CSL participation among undergraduate nursing students at a minority-focused event.Materials and Methods: The International Nursing Students Association (INSA) organized a health screening targeted towards minority populations at the 2017 Asian Festival. Students were provided with orientation and practice to conduct the screening. They were also given a chance to experience the many activities of the festival. Following the screening, the student volunteers (N=12) were surveyed to identify motivators for CSL participation; completed a survey for health screening skills and transcultural competencies before and after the event; and wrote a 6-word reflection. Quantitative data were statistically analyzed; qualitative data were analyzed for emerging themes.

Results: The predominantly female minority students (83%) joined the CSL activity for personal improvement (50%), commitment to the community (33%), and professional improvement (16%). They had significant (p<0.05) improvement in clinical skills and transcultural competencies. Reflection themes were congruent with the development of clinical skills, contribution to community health promotion, and cultural appreciation.

Conclusions: This extracurricular CSL activity improved nursing skills, transcultural competencies, community health promotion, and cultural appreciation. Knowledge of motivators can develop strategies to enhance student participation. Extracurricular CSL activities could be an avenue to integrate nursing education into real-world experiences, providing care for diverse populations.

Keywords: community service learning, undergraduate nursing students, benefits, motivators, student organization

Introduction

The minority populations in the United States (US) continue to grow in recent years [2]. The US Census Bureau predicts that the US ethnic minority population will continue to grow to become half of the general population over the next three decades [1]. Unfortunately, the US minority populations experience significant health disparities, with poor health outcomes [1,3]. There is a need to increase the pool of culturally proficient health care professionals who could address the needs of these vulnerable populations. Culturally proficient nurses are especially needed to provide quality front line care.Schools of higher education can implement practices that promote educationally purposeful extracurricular activities within the context of their campus communities. The educational preparation of health care professionals can influence the development of cultural proficiency among future health care providers. Health professions education has been considered as a critical and potentially most effective intervention to eliminate health care disparities [4]. Community service learning (CSL) is a tool that can be utilized to connect academic content learned by students to community-based projects to improve learning outcomes [5]. Service learning is a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities [6]. CSL is a valuable learning tool and an effective strategy for engaging students. CSL activities provide opportunities for the student to work and serve the community and expose the students to the realities of health promotion and disease prevention [4,7-8].

Outside of the classroom, students can also be engaged in CSL activities through student organizations, providing them with more opportunities to be involved with the community.

Participation in minority organized events allows for unique immersive cultural encounters that are essential for learning about cultural diversity and health disparity issues. Exposure to a diverse population and serving in an authentic environment can provide opportunities for students to understand the holistic and inclusive nature of cultural events, which can contribute to their academic learning and enhancement of their personal and social d evelopment [4,7-9]. In addition to enhancing and reinforcing academic education, personal and interpersonal development, as well as community engagement, has also been identified as significant benefits of participating in CSL activities [9-11]. However, despite these documented positive effects of CSL, student participation in extracurricular CSL activities organized by student organizations is not well documented. It is not known what motivates students to participate in these activities. The International Nursing Students Association (INSA) of the University of Texas Health at San Antonio, in its eight years of existence, have consistently organized 2-4 CSL health screenings per year during community events held by or for minority populations. Participation in these events by nursing students is relatively poor. Knowledge of students' motivating factors and perceived benefits regarding extracurricular CSL projects may improve student involvement, and inform the planning of these events. According to Cone and Harris’ Six Stage Lens theoretical model for service learning, individual, interpersonal, and social-cultural aspects influence the nature of CSL [7]. The student’s value system, individual characteristics, and past experiences may motivate participation in the CSL activity. The type of preparation, mentorship, and characteristics of CSL activity would influence the benefits of the CSL experience. Hence, this evaluative study aims to determine the nursing students' motivating factors and perceived benefits from participating in an extracurricular CSL activity at an Asian Festival.

Materials and Methods

Setting

The International Nursing Students Association (INSA) of the University of Texas Health San Antonio is an extracurricular student organization run by undergraduate nursing students, with guidance from a faculty advisor. The Baccalaureate Nursing program of this university is an upper-division program leading to a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree. Candidates for the program take their first two (i.e., freshman and sophomore) years of general education credits at any accredited college of their choice [12].For this project, INSA organized the free health screening for the 2017 Asian Festival in collaboration with the Institute of Texan Cultures (ITC) on February 4, 2017. The ITC hosts the annual Asian Festival in San Antonio, Texas to celebrate and showcase the unique cultures and traditions of the Asian community [13]. Advertisements for health screening student volunteers were sent out via student cohort Facebook pages and through the school-wide e-mail distribution list to potentially reach all of the 757 enrolled students (undergraduate students = 533; graduate students = 224) for the Spring 2017 semester.

The health screening was held from 10 am to 3 pm, and was open to all attendees of the festival. Undergraduate BSN students (N=17) volunteered to conduct the health screening which consisted of obtaining the health history, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and blood glucose determination. Appropriate health education from the health history and health screening results were provided to all festival attendees along with tools to improve health literacy using "Ask Me 3™" [14,15] and to detect signs of stroke [16]. Ask Me 3™ is an educational program that encourages patients and families to ask three specific questions to their healthcare providers: 1) What is my main problem? 2) What do I need to do? 3) Why is it important for me to do this? [15]. Studies have shown that patients who use the Ask Me 3™ tool had improved patient-provider communication; the tool empowered the patients to ask questions to help them understand better their health condition [14,15]

Before the event, an orientation session was held to inform student volunteers of the health screening activities and their respective roles and responsibilities. The screening included three stations: station 1- health history and BMI determination; station 2- blood pressure and blood glucose screenings; and station 3- health education (including the provision of Ask Me 3™ and stroke sign tools). All volunteers were initially allowed to choose a station and were encouraged to rotate between stations which provided an opportunity for the students to practice a variety of skills.

Following the CSL event, the volunteers were asked to complete an anonymous survey that included demographic information (i.e., gender, age, and ethnicity), their nursing program (i.e., traditional track or accelerated track), graduate specialty (if they are in graduate school), semester level, and previous CSL experience. The survey also asked the volunteers to identify their primary motivation for participating in the CSL activity, with options including personal improvement (learning new things/ideas/culture), professional improvement (course requirement/include activity in resume), commitment to organization (show active participation to organization’s activity,) commitment to community (sense of “giving back”/community service), cultural curiosity/awareness and understanding (experience the community), curiosity (“What is this all about?”), or others (which the volunteers were asked to indicate). Additionally, the students were asked to rate, using 0-5 Likert-type scale (where 0=N/A, 1=poor to 5=highest), their health screening skills (i.e., health history and assessment, blood pressure, and blood glucose) and transcultural competencies (i.e., knowledge, understanding, communication, and proficiency). Finally, the student volunteers were asked to compose a 6-word reflection story [17] based on their experience from the CSL activity [18].

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas (UT) Health San Antonio approved the use of the health screening data as program evaluation of a health surveillance activity.Data analysis

Twelve of the 17 student volunteers completed the evaluation survey. The data were initially inputted into an Excel spreadsheet and subsequently statistically analyzed using Graph-pad Prism (V6.07, Graph-pad Software). All data were initially tested for central tendencies and Gaussian distribution. Since some data were not normally distributed and due to the ordinal nature of the Likert scale, non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare pre and post scores. Statistical significance is set at p<0.05.For the 6-word story reflections, a two-author team initially analyzed the stories for emerging central themes. Components of each story were then re-analyzed for categorization and discussed at length to reach concordance among theam members. Identified emerging themes were shown to the third author for confirmation. Other issues related to trustworthiness such as credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability were achieved through sharing the results, interpretations, and conclusions to some volunteer student participants. The 6-word stories were then entered into Wordle [19], a program that generates word clouds based on the text provided. The visual word cloud created showcases the prominence of the most frequent words used.

Results

Demographics

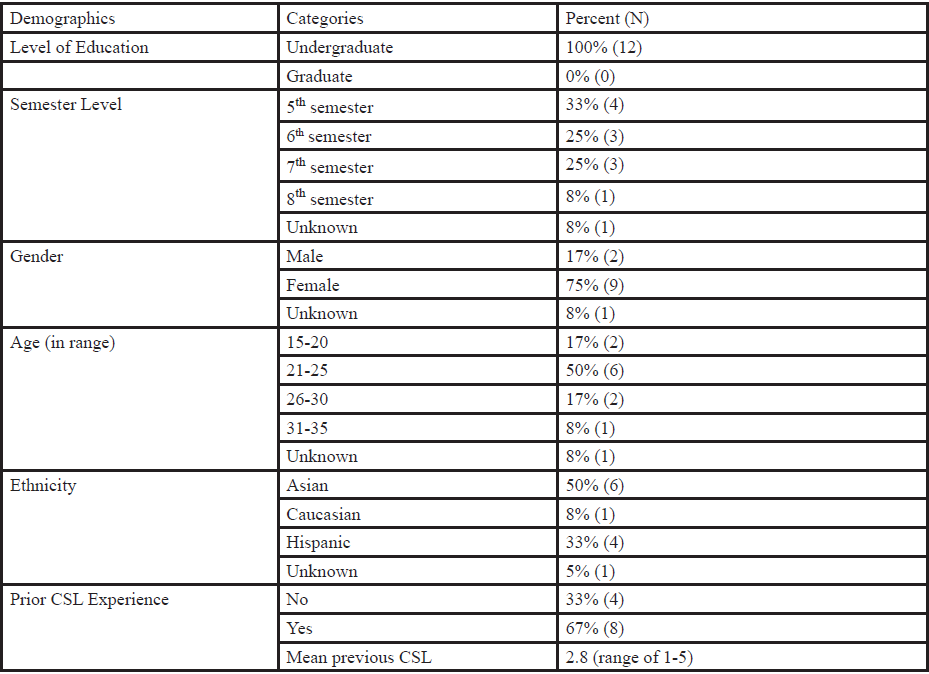

Table 1 shows the summary of the demographic profile of the student volunteers. Student volunteers who participated in the evaluation survey (N=12) consist mainly of female (79%) undergraduate BSN students from various semesters of the BSN Program (semester 5 to semester 8), mean age was 23.9 (range = 19–34 years old). Majority of the volunteers were from minority populations—Asian (50%), Caucasian (8%), Hispanic (33%), and unknown (8%), who did not indicate their ethnicity. Eight of the volunteers had previous CSL experience; 3 of these experiences were from past INSA CSL activities. Four of the student volunteers did not have prior CSL experience.Main motivation

As shown in Figure 1, personal improvement (50%) was identified to be the primary motivating factor of nursing students for joining the extracurricular CSL activity. Commitment to the community (33%) was the second most frequently chosen motivator, with professional improvement (16%) coming in at third.Clinical skills

Figure 2 shows the calculated median of self-rating scores for clinical skills pre- and post-health screening. Although there was a trend for increase in ratings for all health screening skills, i.e., health history, blood pressure, and blood glucose determination. Mann-Whitney tests for pre- and post- health screening scores show that there was a significant increase in rating for blood pressure skills (p =0.007), but not with health history and glucose screening.

Figure 2: Student volunteers’ response regarding their health screening skills before and after the activity. *p<0.05 using Mann-Whitney test to compare before and after scores.

Transcultural competencies

For the transcultural competencies, there was also a general pattern of increase in scores following the health screening activity (Figure 3). Mann-Whitney analysis of the difference between pre and post activity scores revealed significant differences with transcultural knowledge (p=0.022), and transcultural communication (p=0.024). Interestingly, the differences between pre and post activity ratings for transcultural understanding and cultural proficiency almost reached significant levels at p=0.053 and p=0.056, respectively. There was no significant difference between the pre and post activity ratings for social justice.

Figure 3: Student volunteers’ survey response regarding their transcultural competency skills before and after the activity. *p<0.05 using Mann-Whitney test to compare before and after scores.

Reflections

Table 2 shows the 6-word reflection stories shared by 11 participants (1 participant did not write a story). These stories revealed themes congruent with an improvement of clinical skills, positive experience, community health promotion, and cultural experience (see Table 2). The word cloud generated by Wordle is shown in Figure 4, with prominent words such as blood pressure, improvement, health, and fun.Discussion

This study aims to determine the motivating factors and perceived benefits of participating in an extracurricular CSL activity at an Asian Festival among undergraduate nursing students. The self-reported motivations for participation were: personal improvement, commitment to the community, and professional improvement. The student volunteers also reported improvement in clinical skills and transcultural competencies.Personal improvement is the primary motivator for this group of undergraduate nursing students to participate in this extracurricular CSL activity. In the survey, personal improvement was described as learning new things, ideas, or culture. The second strongest motivator is the commitment to the community, described as a sense of "giving back" or community service. These results are congruent with other studies that found internal factors (i.e., altruism, duty, self-expansion) to be the strongest motivators for students to participate in community service [20-23]. However, all of these studies were among college students, but not nursing; and the CSL activities were part of the graded curriculum. This study identified critical motivators for nursing undergraduate students to participate in a purely extracurricular activity, i.e., with no grades. There is minimal literature on this topic. Lapiz-Bluhm and Woosley [7] reported that undergraduate nursing students are motivated to participate in extracurricular activities mainly due to professional improvement (23%), personal improvement (21%), and commitment to organization (15%), commitment to community (18%), cultural awareness (11%) and curiosity (9%) [7]. The difference in results may be accounted for in terms of the difference in ages between the two populations where the current study has a younger demographic (range= 19-34 vs. 19-42 years of age), size of the sample (12 vs. 32), previous CSL experience (8 vs. 18), and ethnicity composition [7].

Darby and colleagues [24] found that college students become more motivated to partake in community service when "they enjoy their experience, have an interest in helping people… and feel a sense of responsibility to the community." Another study found that high school students that continued to partake in community service activities in college were driven by internal factors [22]. Personal and emotional investments in the community encourage students to serve the people in these communities. Thus, students' exposure to various activities would help them form relationships with community partners and its members. Student-led organizations, such as INSA, is one way to help students connect with various community partners through extracurricular CSL activities. Jones and Hill [22] found that visibility and accessibility of community service opportunities influenced student participation. Ferrari & Bristow [21], in their survey of psychology students, found that altruistic campus atmosphere predicted the students' motivations for community service involvement. Being a part of specific programs and activities, such as fraternities/sororities are also an effective influence on the students' involvement in community service [22,23]. This study also found the commitment to the community to be the second most frequent motivator for nursing students. The current results are different from other studies that determine involvement through club or classes and learning new experience to be the second most frequent motivators [23]. Being mindful of the motivating factors behind CSL involvement by students may help student leaders, faculty, and community partners in planning community service events to increase student participation. Student-led organizations and faculty can organize activities tailored to the interests of the students that would entice them to partake in CSL events.

Although there was a general pattern of increasing scores post-CSL activity regarding the student volunteers' clinical skills, the increase was not significant except for blood pressure screening skills. This result is in contrast to Lapiz-Bluhm and Woosley’s [7] previous findings of a significant increase in self-reported scores of first-time student volunteers' clinical skills (i.e., including health history, blood pressure, and blood glucose determination) after participating in CSL activity. It is worth noting that there was not a significant difference in the self-reported scores of experienced student volunteers. The lack of statistical difference for the glucose screening skill scores may be due to the ceiling effect; the students already rated themselves high at baseline. Nevertheless, this current study’s result suggests that participating in a short-term extracurricular CSL activity can help improve nursing students' blood pressure taking skills. These outcomes reflect the students' perceived benefits of the CSL activity in regards to their clinical skills. CSL activities, such as a health screening, not only help nursing students practice their learned skill in a clinical setting, it is a way for them to connect theory and translate them into practice, thus improving learning outcomes. This is similar to other studies that found service learning increased retention of academic contents and increased learning outcomes by helping them see the connection between theory learned in the classroom setting and the clinical work [10,24-27]. CSL activities provide opportunities for nursing students to practice various clinical skills which could help them become even more proficient in these areas.

Similar to the clinical skills scores, there was a tendency for the transcultural competency scores to increase after the health screening. However, only the transcultural knowledge and transcultural communication reached statistical significance. The nature of the CSL activity may have influenced this result. The activities involved in the health screening encouraged the students to communicate and interact with the attendees of the festival throughout the event—from the intake, where the students took the health history of the festival attendees, to the last station where they provided health education. Erickson [28] found that students reported improvement in the communication skills after participating in a service learning project in a non-clinical setting. This result is similar to a previous study by Lapiz-Bluhm and Woosley [7] where they found that both first-time and experienced volunteers reported a significant increase in transcultural knowledge and communication. There was no statistical difference in transcultural understanding and cultural proficiency scores. Failure to reach statistical significance may be because the student volunteers were not given sufficient time with the community. The health screening only lasted for a few hours which may not be adequate time to improve cultural understanding and cultural proficiency. The study’s result is different from other studies that found participating in service learning courses can increase cultural competency and understanding [7,28,29]. The difference in the results may be accounted to the nature of the interventions. The previous studies were conducted using semester-long courses, whereas this study looked at the effects on cultural competencies after one event. The scores for sense of social justice also failed to reach statistical significance. This finding is different from previous studies that showed improvement in civic engagement scores after a service learning course [9,30]. Nokes and colleagues [31] found that civic engagement scores of college students increased after participation in a service learning activity. Groh et al. [30] saw an overall increase in leadership and social justice skills of nursing students following service. Watts et al. [32], in their study of oncology health providers caring for minorities, found that the health providers felt uncertainty and discomfort when caring for minority populations—with cultural and language barriers as some of the main issues. Thus, it is essential that healthcare providers receive training and education tailored to developing cultural awareness and proficiency [32]. Organizing more minority-centered extracurricular CSL activities can provide the students with more opportunities to interact with the minority populations, and help them further improve their transcultural skills and sense of social justice. CSL activities centered on minority populations, such as an Asian Festival, allow students to work in an authentic and immersive environment where they can develop an appreciation of the community they are serving and its cultural background. It can also be a way to introduce nursing students to various cultural values and beliefs, thus helping them develop cultural awareness and help them further enhance their cultural proficiency.

Finally, the students were asked to write a six-word story to reflect on their experience after the health screening. Six-word stories are often attributed to Ernest Hemingway, having been credited for writing "For sale: baby shoes, never worn" [19]. Influenced by the literary legend, Smith magazine founded the Six-word Memoir Project in November 2006 and had since gained prominence in the popular culture [33]. This practice has since found its way in the classroom setting [17,34]. Creating a six-word story is a simple and creative way for students to reflect on their experience. It is important that students critically reflect on their experience as it helps them connect what happens in the community and the academic setting [35]. It is essential for them to internalize their commitment to serving others. The six-word stories written by the student volunteers were inputted into Wordle, a visual cloud generator, to analyze recurring themes. Wordle is a program that produces visual word clouds that showcases the most frequently used words [19]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on CSL reflections to utilize Wordle. More importantly, the word cloud generated revealed themes that were congruent with the results of the survey—with the most frequently used words being "blood pressure," "improved," and “fun." The themes suggest that the students believe they have improved after the CSL activity while having fun doing so.

Conclusion

Extracurricular CSL activities are opportunities for students to be involved in the community and help them form community relationships. The desire to improve on a personal level and to serve the community are some of the strongest motivators for nursing students to be involved in community service activities. CSL activities are beneficial for nursing students to improve clinical skills and transcultural competencies. Therefore, extracurricular activities should afford CSL opportunities to student members especially those in nursing and other health profession students.Acknowledgment

Dr. Lapiz-Bluhm received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Faculty Scholars Program. The Center of Medical Humanities and Ethics of UT Health San Antonio provided funding support for the purchase of consumable materials needed for health screening. We thank the Institute of Texan Cultures, especially Ms. JoAnn Andera, for allowing the International Nursing Students Association (INSA) to perform health screening during the 2017 Asian Festival. We thank Mr. Bryan Ralloma and other INSA student leaders for helping organize the health screening and for providing input on the analysis of qualitative reflections.References

- National Institutes of Health (2013)

Health disparities. National Institutes of Health research portfolio

online reporting tools.

- United States Census Bureau (2014) 2010 census shows America's diversity.

View

-

Nelson AR. Smedley BD, Stith AY (2003) Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

National Acad. Press Washington D.C. View

- Calvillo E, Clark L, Ballantyne JE, Pacquiao D, Purnell LD et al. (2009) Cultural competency in

baccalaureate nursing education. J Transcult Nurs 20: 137-145.View

- Prentice M, Robinson G (2010) Improving student learning outcomes with service learning. Higher Education 148.

View

- Ryan M (2012) Service-learning after learn and serve America. Education Commission of the States, Denver.

View

- Lapiz-Bluhm MD, Weems R, Rendon R, Perez GL (2015) Promoting health literacy through “Ask me 3™”.

J Nurs Pract Appl Rev Res 5: 31-37.View

- Rodriguez YM, Lapiz-Bluhm MD (2018) Community

service learning in undergraduate nursing: Impact and insights among

students. J Nurs Pract Appl Rev Res 8: 27-32.

- Simons L, Cleary B (2006) The influence of service learning on students' personal and social development.

College Teaching 54: 307-319.View

- Brody SM, Wright SC (2004) Expanding the self through service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learn 11: 14-24.

View

- Redman RW, Clark L (2002) Service-learning as a model for integrating social justice in the nursing

curriculum. J Nurs Edu 41: 446.View

- The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (2010) Nursing programs.

- Institute of Texan Cultures. (2017) Asian festival.

- Lapiz-Bluhm MD, Weems R, Rendon R, Perez GL (2015) Promoting health literacy through “Ask me 3™”.

J Nurs Pract Appl & Rev Res 5: 31-37.

- National Patient Safety Foundation (2017) Ask me 3: Good questions for your good health.View

- National Stroke Association (2017) Act FAST.View

- Rich J (2014) Six-word memoirs in the classroom.View

- O’Toole G (2013) For sale baby shoes never worn.

- Feinberg J (2014) Wordle-beautiful word clouds.

View

- Darby A, Longmire-Avital B, Chenault J, Haglund M (2013) Students' motivation in academic service-learning

over the course of the semester. College Student J 47: 185.

View

- Ferrari JR, Bristow MJ (2005) Are we helping them serve others? Student perceptions of campus altruism in

support of community service motives. Education 125: 404-414.

View

- Jones SR, Hill KE (2003). Understanding patterns of commitment: Student motivation for community service involvement.

J Higher Edu 74: 516-539.

View

- Moore EW, Warta S, Erichsen K (2014) College students' volunteering: Factors related to current

volunteering volunteer settings and motives for volunteering. College Student Journal 48: 386-396.

View

- Amerson R (2010) The impact of service-learning on cultural competence. Nursing Education Perspectives 31: 18.

View

- Bassi S (2011) Undergraduate nursing

students' perceptions of service-learning through a school-based

community project. Nursing Education Perspectives 32: 162-167.

View

- Corwin M. Owen D, Perry C (2008) Student service learning and dementia: Bridging classroom and clinical experiences.

J Allied Health 37: 278E-295E.

View

- Hardy MS, Schaen EB (2000) Integrating the classroom and community service: Everyone benefits. Teaching of Psychology 27: 47-49.

- Erickson G (2004) Community health nursing

in a nonclinical setting: Service-learning outcomes of undergraduate

students and clients.

Nurse Educator 29: 54-57.

View

- Worrell-Carlisle P (2005) Service-learning: A tool for developing cultural awareness. Nurse Educator 30:197-202.

View

- Groh CJ, Stallwood LG, Daniels JJ (2011)

Service-learning in nursing education: Its impact on leadership and

social justice. Nursing

Education Perspectives 32: 400-405.

View

- Nokes KM, Nickitas DM. Keida R, Neville S

(2005) Does service-learning increase cultural competency critical

thinking and civic engagement?

J Nurs Edu 44: 65-70.

View

- Watts KJ, Meiser B, Zilliacus E, Kaur R, Taouk M et al. (2017) Communicating with patients from minority

backgrounds: Individual challenges experienced by oncology health professionals. Eur J Oncol Nurs 26: 83-90.

View

- Six-word memoirs from SMITH magazine (2017).

View

- Hamm S (2015) Assign six-word memoirs for reflection and synthesis.

View

- Bailey PA, Carpenter DR, Harrington P (2002)

Theoretical foundations of service-learning in nursing education. J

Nurs Edu 41: 433-436.

View

Integrating Nursing Education in Students’ Extracurricular Activities: Students’ Motivations and Benefits ,

Integrating Nursing Education in Students Extracurricular Activities Students Motivations and Benefits ,

Integrating Nursing Education Students Extracurricular Activities Students Motivations ,

Students Motivations and Benefits Integrating Nursing Education Students Extracurricular Activities ,

Extracurricular Activities Integrating Nursing Education Students Students Motivations and Benefits ,

Integrating Nursing Education in Students Extracurricular Activities ,

Students Motivations and Benefits Integrating Nursing Education in Students Extracurricular Activities ,

Comments

Post a Comment